What do we want? An end to reductionism: Change Everything No 11

When do we want it? NOW!

Book news

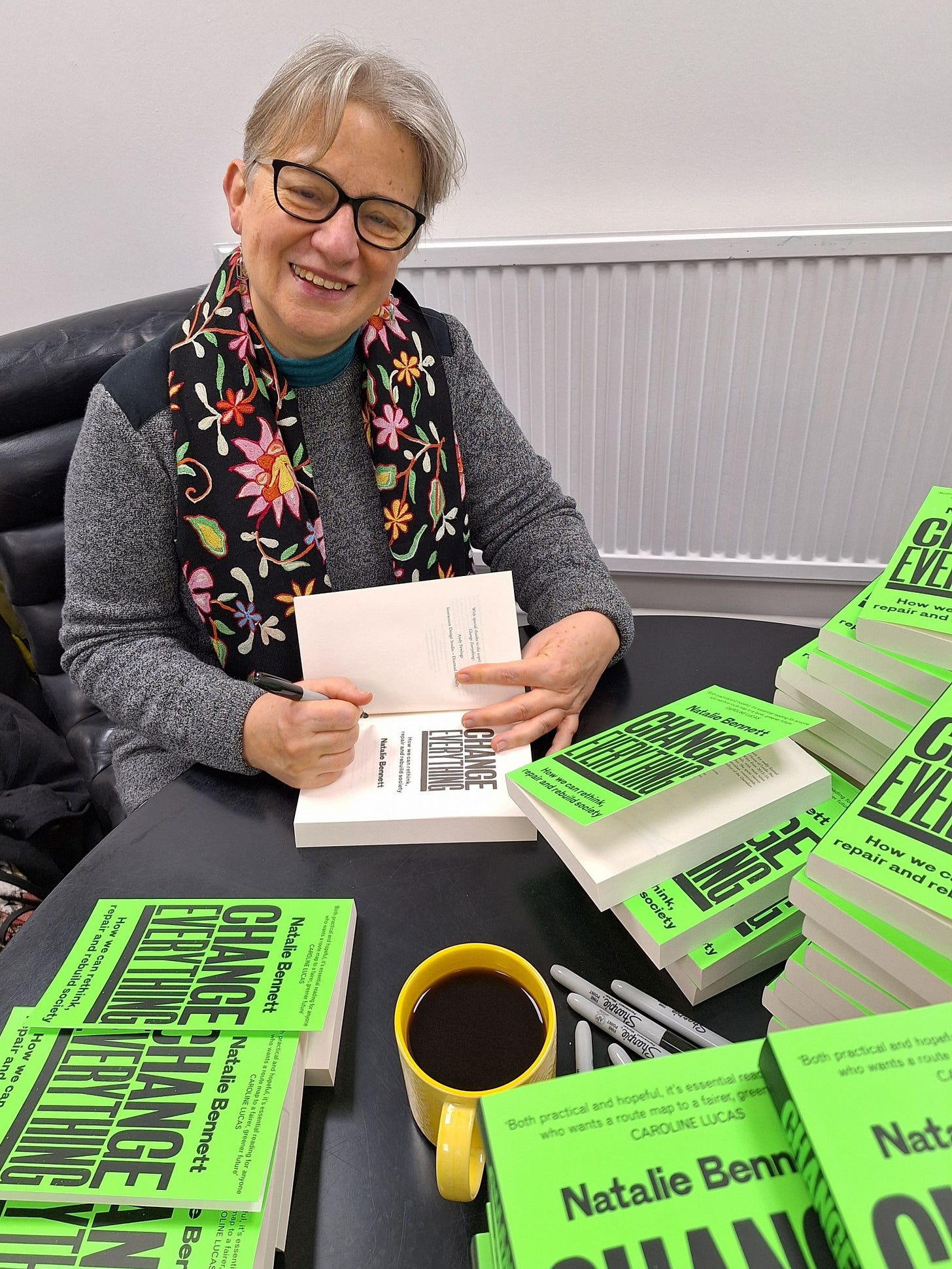

Exciting! I’ve laid hands on an actual physical copy of my forthcoming book (out March 21), for which this newsletter is named. Yes, it is neon green - very green. And those who contributed to getting it published with Unbound will soon be getting signed copies through their letter boxes. (Apparently my signing speed set a new record - that’s what comes of decades of being a journalist writing notes. No guarantees on legibility.) If you’d like to pre-order your copy, and get it in your mail or inbox on publication day, you can order with Unbound now.

Humans are not machines

I knew that politics had really taken over my life back in 2006, when I found myself on holiday in Europe wandering around city streets thinking “oh, that would be a great window for a ‘Vote Green’ poster”. (That was after my first campaign, for Camden council.)

I try not to talk and think about politics all the time, but there’s nothing really, in our age of polycrisis, that doesn’t lead you back to politics. So I was not surprised when I found myself in a brilliant exhibition at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris, of the work of the French-Gabonese artist Myriam Mihondou, that as well as admiring - and feeling - the art, it gave me a new way to look at my current work in the House of Lords, particularly the debate on Thursday on mental health and wellbeing and schools, and the debate coming up tomorrow on medical regulation.

The exhibition is titled “Ilimb, the essence of crying”, (Ilimb being a word in the Punu language, from the South of Gabon, meaning, approximately, tear trails). At the heart of the exhibition, texts explain, is the Moñu, “the matrix stretching through space and time. It encompasses life in all its forms: human, plants and animals”. That’s embodied in a “living sculpture”, which visitors are invited to touch, a great vine stretching the length of the gallery, embedded with a sensor cable, which feeds into the soundtrack of the exhibition. A tap of a ring on the vine sounded like a drum beat, a caress a deep rumble. I watched a child of perhaps four discover the effect with delight, even if Mum had to offer restraint as the exploration went to seeing how loud an impact he could make.

The exhibition also includes clay sculptures, recollecting the pots of the Matsanga weepers that are, we are told “filled with a lifetime of tears”. The artist speaks of how the red colour reminds her of the soil of the area, and its smell after rain. (The words evoked for me a reminder of the smell of the Australian Bush, when after a hot day a storm delivers big thumping drops of rain, that stir the dust rather than settle it.)

The “weepers” in this culture are sometimes mourners at funerals, who accompany “the soul and the spirit of the departed, giving voice to memories and defiantly affirming their existence in the face of death”. But they have many other social roles. As a panel in the exhibition explains “children are initiated by the weeping women. The teaching they provide is fundamental, emboying a knowledge which is at once mystical, scientific and therapeutic”.

That made me think of Thursday’s House debate, in which I focused on how schools have been pushed to stop regarding pupils as living, feeling, complex beings embedded in a (in our case deeply unhealthy) society. Instead schools are pushed to regard pupils as potential exam marks, contributors to places in league tables, empty vessels into which a requisite amount of knowledge is poured then sealed up and shoved out to be economic units.

The traditional education of the weeping women, at least on the account here, seems far more inclusive, supportive, and with knowledge built on what we might call systems thinking, rather than Victorian classifications of subject areas and training for uniformity and conformity.

I think it would be fair to say the House was a bit shocked by my introduction to the debate. Baroness Morris of Yardley, a former Labour Education Secretary, for whom I have the utmost respect, said as much, although going on to agree with a lot of my points, particularly about the damage being done by the pressue of exams. But then many speakers, including from the Tory benches, some sharing family experiences, spoke about how, to quote Tory Lord Wei: “too often, parents find that the imperative schools have to keep children in school and perform in and for exams”. And Baroness Tyler of Enfield (Lib Dem) pointed to the awful statistic: “In a recent survey by Young Minds of more than 14,000 young people, only 3% said educational settings were a positive influence on their mental health.”

It also led me to reflect on a interview I did with Lord Bethell, former Conservative health minister, on Today in Parliament, about medical regulation (starting 10 minutes 42 seconds in), which will be the subject of tomorrow’s debate. Behind some of disagreement was a sense that patients can be treated, classified, managed by their disease or condition, their situation simplified down to treat a single injury or illness, without looking at them as a whole person.

Looking at individual as a series of attributes and results, giving marks and scores, treating people as cogs in a machine - these are all reflective of 20th-century approaches to science, politics and economics, the reductionist approach that has got the world into the state it is now. That has taken away understanding of humanity; it sees workers in Amazon warehouses forced to behave as though they are machines.

That is not how most of humanity has lived for most of our history, as Ilimb reminds us. And what we are doing is deeply unhealthy.

I don’t expect to see a giant protest march coming down Whitehall chanting “What do we want? An end to reductionist thinking! When do we want it? Now!” But we do need to think deeply and widely about how so many systems in our society are terribly unhealthy, for human animals, non-human animals and the ecosystems on which our life is 100% dependent. That does not just mean “fixing” landuse, or slashing carbon emissions to near-zero in a decade, it means, as my book title says, we need to change everything. And our education and health systems are particularly crucial areas for building a healthy, humane future.

Picks of the week

Reading

Soon out in paperback, Meetings with Moths by Katty Baird, I’m recommending you lay hands on a copy not just because it features one of my favourite historical figures, Maria Sibylla Merian, or because you should know more about these wonderfully, ecologically important creatures, but because it is a damn good read. And will give you an ideal dinner party anecdote about why are male moths antennae bigger than females? (I made some notes from it here - which give away the answer.)

Photo by Carol Petri on Unsplash

Listening

Another brilliant New Books Network podcast with Markus Krajewski, author of The Server: A Media History from the Present to the Baroque, who uses the history of servants asks probing questions about the way computer servers (the origin of the term in c. 12th century) are part of our lives today. Thinking about how historical servants - butlers and goverrnesses, footmen and maids - were not mere mechanical tools, but active agents changing the world, so we need to think a lot more about replacing people with “things” and what agency and impacts those things might have. Not directly addressing current debates about “artificial intelligence,” but certainly relevant to it.

Thinking

With the climate emergency destabilising fluvial systems around the world, it is past time we thought, and researched, a lot more about the fungi growing in river sediment, of which we know - such a familiar story - little. "When sediments are exposed to air, these fungi may begin to produce many spores that disperse in search of a more suitable environment, and it is during this dispersion that they can interact with humans and animals” - interact including “infect”.

Researching

The origins of water, and its place in the universe: this is a truly mindblowing topics when you start to get into it, and researchers are finding out a lot more with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) studying protoplanetary disks. It can see ice whereas previous instruments could only see water vapour, and get into the inner regions, previously invisible.

As a piece in Scientifc American (sorry, paywall, but your local library should have it) explains:

Deep within Earth it ensures the lithic lubrication that keeps climate-stabilizing plate tectonics from grinding to a halt—another mechanism that just might be crucial for life. And when frozen as ice it plays a key role in planet formation by providing the glue that helps young worlds grow.

And the conclusion: “Most terrestrial worlds across the cosmos might be born rich, with a wealth of water from the very start.” Take it away, science fiction…

Almost the end

Unfortunately I won’t be able to make it, but there’s what looks like a brilliant seminar tomorrow night (online) at the Institute for Historical Research, “The Games Mistress in Interwar Britain”. The introduction notes: “Some headmistresses placed greater importance upon the character of her games mistress than any other member of staff, because the games mistress interacted with girls in their more spontaneous and unguarded moments; ‘hers was the exceptional opportunity of helping them to play in a manner to show not merely proficiency in games, but character as well’.” Reminds me of Miss Harris and Miss King, who through my high school years definitely encouraged resilience and coming back from knocks.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.