Change Everything No 8: Always intrepid women

Stereotypes about the sex and class of travellers are curiously persistent

Making old discoveries

There are some stories that just keep coming around, discovered anew by not-so inventive journalists at regular intervals. As a former Green Party leader, I’d be able to hold a good knees-up had I got a payment every time a journalist discovered that we had policies on issues other than the environment. (Every time one of these comes out, I’m going to have to send the author a copy of Change Everything, the book - launch just five weeks away now!)

And as a former, and continuing, lone traveller, I’d do equally well with payments for every time I’ve come across a story - as ABC produced this week - saying we’ve discovered “women travel alone”. Yet when I was backpacking alone around Europe in 1990. And my fellow sole travellers were almost all female.

Yet the idea of a traveller is heavily enmeshed with Victorian stereotypes of intrepid explorers, usually male, with the local “bearers” and guides without whom they’d never have got anywhere pushed out of the frame. And the women keep being similarly “disappeared”.

I’ve previously referred to Margery Kempe, the medieval pilgrim who you might just have heard of, but you’re unlikely to have heard of the first woman known to have circumnavigated the world, Jeanne Baret (below). Born to a humble peasant family in deepest rural France, she in 1766 joined Louis Antione de Bouganville’s scientific naval expedition, disguised as a man, and acting as expert assistant (and often nurse) to its naturalist. After his death in Mauritius, she set up as a tavern keeper and businesswoman there, completing her voyage as the wife of a French non-commissioned officer. In 1785, she was granted a substantial pension by the French state, and was nationally famous in her own time, but, as is so often the case with women in history, was then forgotten. Only in the last few years has she been rediscovered.

But you didn’t have to be travelling alone to be adventurous. I love Auðr/Unnr Ketilsdóttir, (“the deep minded” - wouldn’t that be a great sobriquet to have earned). She was the daughter of a Norwegian chieftain and wife of a Norse king in Dublin who after her husband and son were killed “had a ship built secretly in a forest, and when it was completed she loaded it with valuables and prepared for a voyage. She took all her surviving kinsfolk with her.”

Still too, we are hugely classist too, in celebrating “explorers” and “adventurers”, almost invariably from the upper classes. Innumerable youngsters of both sexes have always adventuring, through need, interest, or probably most often a mix of both. The first “Tour de France” was a circuit for apprentices, moving from town to town to learn new skills. Written down by a baker in 1859, the route included 151 towns. Martin Nadaud, age 14, can stand for the many: he left a Limousin hamlet in 1830, dressed by his tearful mother in a top hat, new shoes and a stiff sheep’s wool suit. (From Graham Robb’s The Discovery of France)

Girls did it as a norm too, although for them of course, there were specific risks. In 1794, in the midst of the turbulence of revolution, Margueritte Barrois arrived in Paris from the east of the country, looking for domestic work. A shopboy also from her region, Charles Miquet, on a night when the soldier were roistering noisily in the city, crept along a corridor to “comfort” her. Nine months later she was holding a baby. (That latter tale is from The Fall of Robespierre, a great book about one day - a big day - in Paris.)

A similar regular journalistic shibboleth is the “gosh, people are going out to dinner on their own in restaurants” story. Apparently this is a “trend”. Which would have been news to me, aged 17, when I first dined alone - in the then considered quite high-brow setting of the Travelodge Motel Restaurant in Taree, NSW, Australia, on my way back from moving my grandmother and a significant chunk of her world goods in the back of my small station wagon to Murwillambah. The waiter did snootily seat me in the empty restaurant behind the potted palm and beside the loos. (Yes, I’d certainly resist now, but I’m rather more assertive now.)

Picks of the week

Reading

I seem to have been having lots of chats this week about colonialism and its impacts, so I thought it a good time to return to a very strong “must-read” recommendation, Imperial Mud: The Fight for the Fens, by James Boyce, which I reviewed for Resurgence Magazine.

Ireland is often described as having been England’s oldest colony (as in this recent New Books Network podcast), and rightly. But there was colonialism on this island, the takeover of the financiers of the City of the rest of the country, as well. It is possible to look at the history of Scotland and Wales that way, but also to the fenlands of eastern England, where a distinct culture, with its own dialect, way of life and ecosystem was swept aside - despite often valiant and temporarily successful resistance.

This is really direct action from people defending their land (the labourers had to be imported from elsewhere in England because locals would not do the work):

“At 2pm on 13 August 1628 in a field south of Haxey, a group of women distracted drainage workers with verbal abuse while the men ambushed them from behind and started throwing volleys of stones. Some of Vermuyden’s men were thrown into the dyke and held under with long poles. According to the official report, threats were made to break limbs and burn the men who did not leave the Isle ... although the intent seems to have been only to frighten the conscripted workers since no one was maimed or killed. Once the work site had been captured, drainage works were destroyed, and wheelbarrows and other implements burned. It was estimated that between 300 and 500 people were involved in the action.”

Listening

Just caught up with the London Review of Books podcast on the War in Tigray. It not only charts the little covered, enormously bloody, internal conflict from 2020-22 (as many as 600,000 dead from direct injuries and famine), but also reminds us that this is on the “other side” of the Red Sea, where, right now, as Tom Stevenson explains, British pilots are flying mammothly long missions from Cyprus to fire very expensive missiles into Yemeni farm houses to target what are thought to be Houthi targets. This central space for international trade, so key to the current global economic model, could hardly be more volatile.

In the House of Lords this week, I questioned the government’s military intentions in the Red Sea and its meaning when it said Houthi capacity had not been “fully diminshed”. The minister’s response: “Military action is unlikely to achieve our aims.” (The statement in the Commons contained the monumentally stupid claim that “Freedom of navigation has been a cornerstone of civilisation since time immemorial” - which I challenged with a bit of, you know, actual history.)

Playing

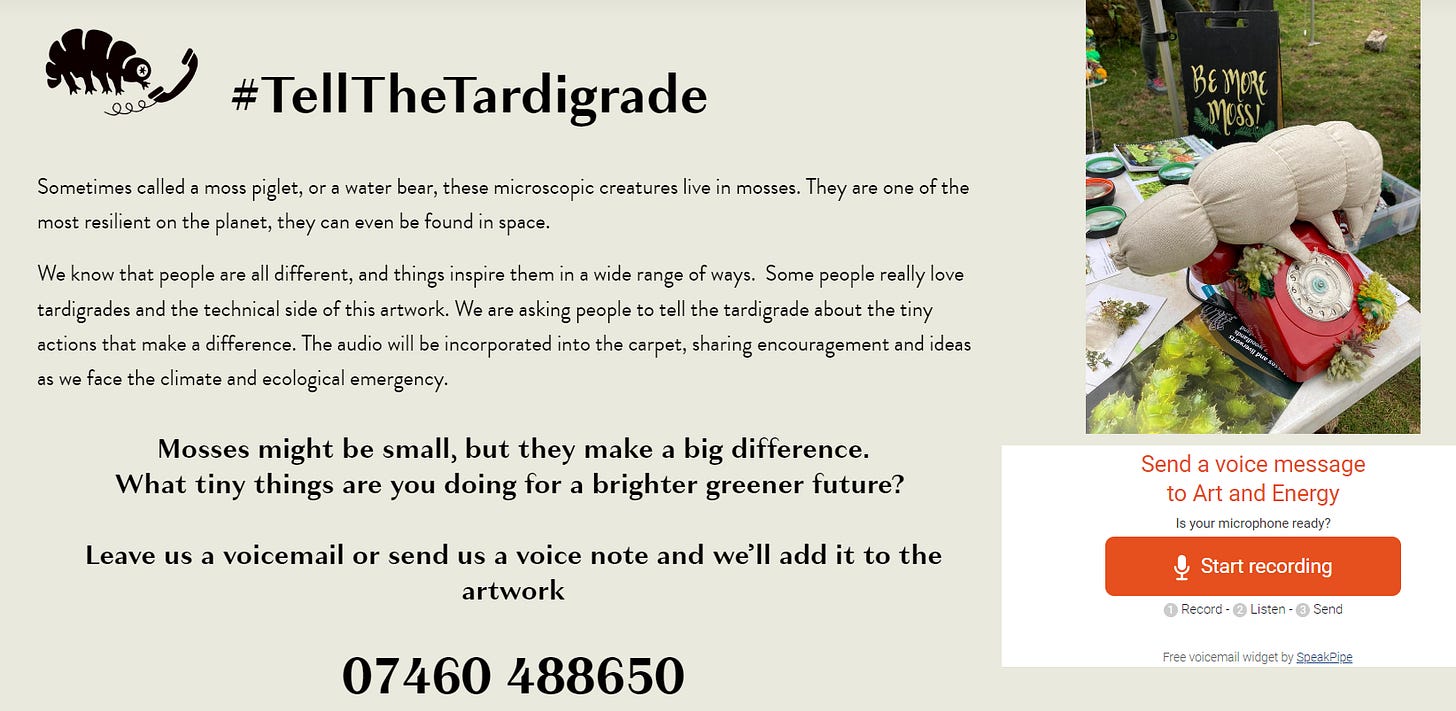

What would you tell a tardigrade? Great idea from Art and Energy for collaborative art. (Thanks Chloe for the tip.)

Thinking

Over 60s are expected to make up more than 20% of India’s population by 2050, so there is considerable interest in the rates of neurocognitive impairment and dementia in its society. A study published in a respected journal found alarming current levels. But some researchers have - with very good reason — questioned the results, pointing out that using test methods developed for societies with high levels of formal education and literacy on societies that don’t - nearly half of the subjects in this study were either illiterate or had no formal education - is unlikely to produce meaningful results.

As I often reflect, formal test and exams test how well you do tests and exams; the results have little or no meaning beyond that. (And I can say that as someone who all-too-frequently has done well in exams by being motivated to do well and having tricks and techniques to get marks, rather than actually understanding the subject.)

Almost the end

The Atlantic produces a lot of good writing. Often, they cover worlds very different to the one in which I live, such as this article on the laboratory-made diamonds market. The word I most associate with diamond is “blood” - but I don’t find turning them down on a moral basis difficult. They are dull, unexciting, colourless glitz, not to mention the “keeping up with the Joneses” underlying ethos. As The Atlantic puts it: “Lots of people want to give or receive big diamonds because of their implications, not in spite of them—especially when it comes to wedding jewelry, where price is so freighted with meaning.”

How much more interesting are multivarious gemstones, often described as “semi-precious” stones. And you don’t have to take out a loan to buy them.

And really finally,

Happy Losar (Tibetan New Year).

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.