Change Everything No 6: The more things stay the same ... Britain 1962-65 and today

Welcome to this bonus mid-week edition, containing a very extended book recommendation and reflection.

The more things stay the same

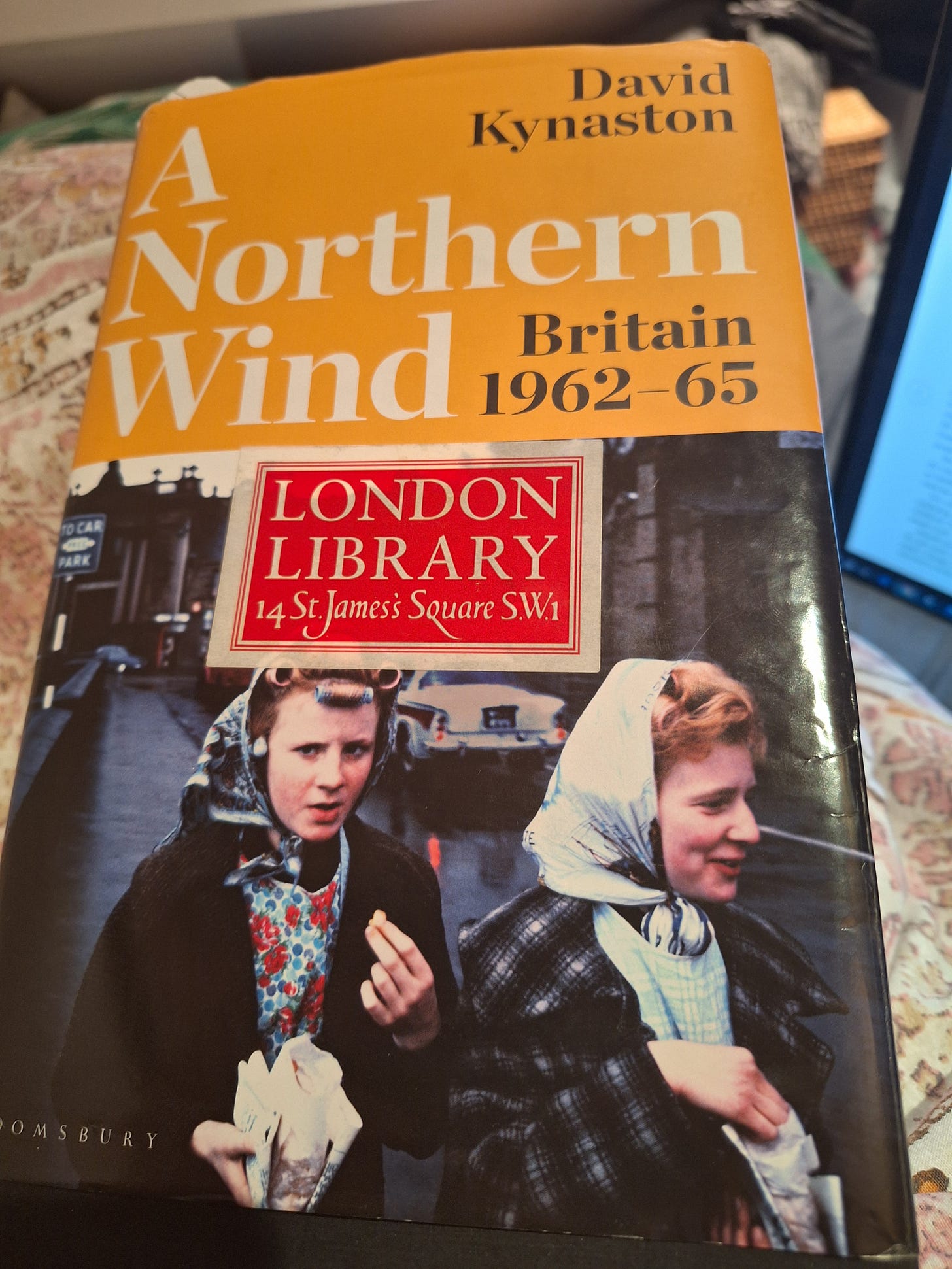

The seventh book in a mammoth series, David Kynaston’s A Northern Wind: Britain 1962-65, is the source of the main body of this extra mid-week edition of Change Everything. Drawing heavily on Mass Observation diarists and media monitoring (audience reaction can be a hoot), interspersed with the politics and culture of the day (so the rise of the Beatles, and their contrast with The Rolling Stones has a prominent place), media and academic accounts, it takes the reader into the texture and the taste of life, and the frequent misery (particularly of women trapped in social expectations of propriety and subservience.) And highly readable, as another commentator remarks. It stops the year before I was born, and so to me paints a picture (if from the other side of the world) of the circumstances in which my teenage Mum was struggling to find a place - which was what led to my coming into existence, getting pregnant being the only way she could escape from an unhappy home life.

But what is striking is how many of the political problems the country was wrestling with them failed to be in any way resolved in the now nearly six decades since. And how the “solutions” that were emerging - Beeching railway cuts, redevelopment of town centres, the pursuit of growth - produced some of today’s great still unresolved crises.

This is not a book review - well, hey, it is brilliant, like all of the series (review done!) - but a record of some elements that struck me as remaining particularly relevant today.

Divided England

The North-South divide as a cause of great political angst and debate in the period covered by The Northern Wind. Kynaston quotes David Holden from the Guardian:

“The North is crippled with the burden of the industrial revolution to such an extent that the South hardly begins to understand. Virtually the whole social capital of the northern towns, from the antiquated town halls of marble and millstone grit to the grimy schoolhouses among the streets of backs-to-backs is of Victorian origin and desperately in need of renewal. The sheer mental depressions that the sight of this decay induces is enough to deter most professional people in the South from ever settling in these towns - and, especially, to encourage the best local boys to get out and stay out as fast as they can.” (p. 37)

By early 1963, Macmillan appointed Lord Hailsham to have particular responsibility for the North East. “He was shocked by the dereliction… But Hailsham also - foolishly - spent most of his tour wearing a cloth cap, viewed locally as a ridiculous gimmick and even, fairly or unfairly, as condescending; and it prompted the song ‘Little Cloth Cap’ by the Newcastle folk singer Alex Glasgow, with its opening line. ‘If you ever go to Tyneside, let me give you some advice’ [A good bit of advice I got early in politics, never wear a hat that suggests you are acting a part. In fact I’ve never found a hat that works for politics…]

But this was serious - and still all too familiar in 2024. “Jack Ashley’s evocative and moving documentary, Waiting for Work, about life in West Hartlepool, where one in nine of the town’s working population were signing on twice a week at the Labour Exchange. ‘You start to think you’re a sort of parasite, living on the backs of your fellow-men.’ said one of those unemployed; another sequence showed a couple living on one meal a day and chopping up the furniture for firewood” (p. 132-3)

Seaton Carew beach, near Hartlepool Photo by Aleks Marinkovic on Unsplash

“Liverpool University’s ‘Crown Street’ survey “Living alone at 75 Bamber Street, and paying rent of 27 s 5d a week, the 66-year-old widower there was just about surviving as a self-employed hawker (cloths & brushes, from a suitcase’)… Furnishings: ‘Very meagre. Only the necessities. Mr B sleeps in his living room as the rest of the house is so damp… A fire was laid but not lighted despite the awful cold.’… Mr B: Keeps to himself and does not bother with the neighbours. He has relatives in Bootle and Manchester but does not bother with them. He spent Xmas on his own. He does not know when he is too old to look after himself… The house is in a shocking condition. There is a big hole in the bedroom ceiling where it has rained in. The bathroom is also unusable.” (p. 135)

The welfare state was subjected too to a considerable degree of the tensions of today. “In around 1960, interviews with 144 people of varying backgrounds … two-ifths wanting ‘more stringent enquiry' into people receiving benefits, especially national assistance; in 1961 a survey … mainly seeking the view of mothers, found high percentages from different social classes wanting the government to spend the same or more; and in 1962 an opinion poll relating specifically to the NHS found 89% satisfied and only 11% dissastisfied, rising to 13% among the ‘lower class’.” (pp. 104-5)

Yet there was already understanding of the inadequacy of the Beveridge welfare settlement, that women campaigners had identified from the start, which again feels very 2024.

“New Frontiers for Social Security, aimed modestly at ‘the abolition of poverty that exists in the midst of plenty’, was the title of Labour’s policy document launched in April 1963 by Richard Crosman, and aiming to fill a vacuum in government thinking. “We are detremined,” he told a press conference, “to get what Beveridge never got - subsistence for everybody.” .. for the medium to long term, an attempt to close the huge gap between the two classes of pensioners (i.e. those with an occupational pension and those entirely dependent on a state pension) through a superannuation scheme leading in effect to half-pay pensions; while for the short term, ‘a special rescue operation’ was proposed in the form of ‘a quite novel kind of Income guarantee which fixes a minimum income level and ensures that the necessary suppplementary benefit will be paid as of right, and without investigation by the National Assistance Board to everyone whose total income falls below that level.” (p. 52-3) Not quite a universal basic income, but heading that way.

Yet the foundations of consumer society were being laid. “This was undoubtedly an age of ever-increasing consumption. The figures for volume of consumption in 1965 speak for themselves (on the basis that 1950, 15 years earlier, equals 100): Food 125.7, Drink, tobacco 129.8, Clothing 135.4, Housing and maintenance 137.3, Furniture, household goods 142.4, Radio, electrical 281.4, Motor vehicles and fuel 684.1. (p397)

Failling the young

Schooling was heading towards the widespread - but not complete - end of grammar schools, a move with which Kynaston clearly, and rightly has great sympathy. The desire for conformity, in both grammars and secondary moderns - many echoes again of today - did great damage.

One tale sums it up, telling the story of the future educational sociologist Stephen Ball. “From a skilled working-class background, and having got through the 11-plus, he had gone the previous year to Bishopshalt Grammar School Uxbridge, second-tier in academic achievement but first-tier in keeping up traditions.

Adrift in an alien world of gowns, masters, Latin and cross-country running, Michael Cornes and I were the only working-class boys in our year… The other boys, none of whom very often acknowledged our existence, were almost without exception, it seemed, the sons of lawyers, doctors or stockbrokers. The teaching was dull, didactic, and repetitive. Talk, board writing and snap questions. I was now a ‘fish out of water’, frightened, isolated and very ill at ease… I assumed the mantle of school failure bt the end of the first week. Much of my time at home was spent struggling with gnomic homework tasks, which made little sense to me and for which my parents were unable to give much practical help. Even my facility with words now seemed inadequate. My practical sense had no purcahse on this world of middle-class taste, entitlement and easy accomplishment. I was lonely, unhappy and increasingly alienated.” (p. 97)

Or to the secondary modern: “John Webb, who had attended a secondary modern himself, wrote a sociological essay depicting life there as, on the boys’ side, “almost a guerrilla war against the teacher’s standards - a ragged, intermittant fight to be oneself by being spontaneous and irrespressible and by breaking rules,’ each bout usually ending with ‘the ritual caning and telling off”. (p. 99)

Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash

Yet today, is it so different? As I was writing this, an edition of the Sheffield Tribune arrived in my inbox, reflecting on the controversy around Mercia School in Sheffield, with its rigid rules and exams focus.

For those who think there’s something new about young people getting involved in politics while still at school, there’s a corrective. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, some 250 girls from Mynyddbach Comprehensive School in Swansea “swarmed out of their classes in protest”. (p. 15) Reactions from some sound awfully familiar, however, the local paper quoting a neighbour: ““Their conduct has been deplorable and their language foul. I have never seen anything like it before. I’m sure most of them don’t know what it’s all about. Strong action is bound to be taken against them.”

But there were in fact protests around the country. Future novelist, the late Beryl Bainbridge, was marching around Liverpool in a 200-strong processions “chanting stop this madmess”. One diarist asked “what should the old make H-bombs and use them when the young haven’t lived”. [I once had the pleasure of canvassing Bainbridge for a local election in her Albert Street, Camden, home, trying not to be distracted by the head of the stuffed bison peering over her shoulder.]

A world of discrimination

“One regional quirk - though perhaps not entirely an outlier - by spring 1963 was the Bristol Omnibus Company’s continuing refusal to employ non-white bus crews…. ‘It is true,’ Patey continued, ‘that London Transport employ a large coloured staff. They even have recruiting offices in Jamaica, and they subsidise the fares to Britain of their new coloured employees’… The upshot of a tense week - involving national attention, strong support for the boycott from local students, and a well-judged intervention by the famous ex-cricketer Sir Learie Constantine, now High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago - was an assurance by the company that it would no longer maintain a colour bar. (pp. 175-6) Notably a letter in the local paper reminds us that knowledge of, and hatred of the city’s most famous slavetrader is nothing new. letter “from Tynte Avenue in Hartcliffe: ‘Edward Colston, famous in this city, was a slave trader. He split up loved ones. Families never saw one another after he passed their way. We should be grateful that these dark people should work with us.”

Disasters of ‘modernity’

We’re still paying, and seeking to undo, the damage of some of the decisions made in this period, notably the Beeching report.

“The Sunday Times’s William Rees-Mogg [yes, his father] predictably agreed with the plan’s main thrust (‘No Choice But Beeching’)… What about the PM? At least one of his biographers (D.R. Thompson) is puzzled that Macmillan (‘a railway man through and through) gave the report his full backing, as did the government generally. The answer surely lies in the various leaflets that his party rapdily began to distribute… Each leaflet carried in bod type the slogan “Conservatives believe in modernzing Britain’ - a slogan widely assumed to be the seductive message of the moment. Or as the Duke of Devonshire, Macmillan’s nephew as well as ministerial colleague, put it to the annual dinner of the Traders’ Road Transport Association, the Beeching report was a ‘symbol of the future’; and future historians would look upon it as a ‘first clarion call on which we stopped resting on the laurels of the industrial revolution to look forward to new industrial ideals’. (p. 158)

Photo by Kari Shea on Unsplash

With the added agony of the creation of the now so-cursed Euston station “Euston Station is in chaos,’ noted one diarist, an RAF officer, on Maundy Thursday. "‘Plans to rebuild the whole area well under way and it may be beneficial when a new glass and chrome structure replaces Victorian solidarity.” (p. 170)

So with much “town planning” of the period.

“All change in Kingston, too, where on 30 May a public meeting was held at the Guildhall to discuss the plan for comprehensively redeveloping the town centre. Lionel Hill of East Molesey, in a recently published letter of protest, had called it ‘incredibly bad’, bearing all the stamp of the modern planners’ preoccupation with four things: fast motor roads, car parks, shopping centres and office blocks’. ‘A town built on this concept,’ declared Hill, ‘can have no soul, no civic pride and no history.’ In another letter, Roy Plumley .. had flatly called the plan ‘ruthless and tasteless…. a monument to greed and commercialism’. ‘Not one person from the floor,’ reported the Surrey Chronicle, ‘had a good word to say about it, many were strongly critical and, from their applause, most people were right behind the critics.’ Crucially, though, the criticism that was aired was seldom broad-based. Instead, ‘speaker after speaker rose to bring up points of detail and ask what the local authorities were doing to safeguard individual interests’… all those expressions of individual will meant that more often than not the general will could safely be ignored.” (p. 183)

And yet some of the solutions that we are only now exploring. Fascinating to learn “back in 1962, the transport minister, Ernest Marples, had commissioned R.J.Smeed, deputy director of the British Road Research Laboratory, to study possible methods of charging for road use; and on 10 June the government belatedly and reluctantly published his report. ‘10s AN HOUR TO DRIVE IN TOWN CENTRES,’ was the Daily Telegraph’s headline about the ‘revolutionary road pricing system’ advocated by Smeed, involving ‘drivers paying through meters in their vehicles’, But with an election looming, Marples now opted for the safety of the long grass. “Road-pricing is a considerable time ahead, if it comes at all,” he told a press conference … Still, the problem of road congestion was unlikely to go away'; and even the Telegraph, definitely the motorists’ friend, conceded that ‘the consequences of doing nothing could be far more frightening than the Smeed Report.’. (pp. 424-5)

And our continuing obsession with growth. It dates too to this period.

“Across developed economies in the first half of the 1960s, targets for growth suddenly seemed all-important, especially after the newly founded OECD had in 1961 adopted growth as the goal of all economic policy, with full employment no longer being considered as a sufficient end in its own right. In fact, Britain’s annual rate of growth between 1957 and 1965 of 3.2 per cent represented the economy’s fastest rate of growth since 1870,; but the problem was that rival economies were growing appreciably faster - to such an extent that Labour, in its election manifesto, would be able to claim that ‘if we had kept up with the rest of Western Europe since 1951, our national income in 1964 would be one third more than it is’… a Labour government would be able to reverse this relative decline, essentially through deeply and permanently modernising the economy.” (p. 438)

Lost worlds

Yet, sometimes it has to be acknowledged, Kynaston is very much charting another world.

“Members of the Bradford City Council had a long and emotive discussion about the future of the Leeds Road Wash-house, the proposed demolition of which - in order to be replaced by a purpose-built laundrette - had the previous week provoked some 250 people (almost entirely women) to turn out on a snowy, frosty night in order to object. Arguing strongly for refurbishment, Alderman D. Black, a veteran on the Council, emphasised that ‘a wash-house cleaned, boiled and dried clothes perfectly’, whereas ‘a laundrette did not’ - that in fact it was ‘just the easy way out’. … it did the business, expevially with its drying racks - and in this respect anyway there was little or no appetite for the age of automation.”

Coincidentally, a post about a modern-day attempt to recreate the community spirit of the washhouse in a laundrette, Kitty’s in Everton, arrived in my inbox as I was writing this Substack.

And some things have moved on positively. “At one of Oxford University’s women’s colleges, St Hilda’s… formal consideration began of whether a pregnant undergraduate, Julia Ball.am, could return in October for her second year, with the governing body soon afterwards narrowly deciding (almost without precedence) that she could, provided she was married by then”. (p 428)

Plus ca change

We don’t seem to get much comparison of the circumstances of today with this period, but whether UK politics or external instability (not just the Cuban missile crisis but the fall of Khrushchev and the first Chinese atomic bomb) the parallels are all too evident.

“From Thursday, 6 June, the day after Profumo’s resignation, it was open season, as the popular press gave blanket coverage - sometimes factual, very often less so - to the story. Chapman Pincher in that day’s Express revealed what Profumo had said to him shortly after the March denial (‘who is going to believe Christine Keeler’s word against mine?) but it was the Mirror which stole much of the thunder with its front page editorial….’All power corrupts - and the Tories have been in power for nearly 12 years. They are certainly enduring their full quota of fallen idols, whited sepulchres and off-white morals.’ … BBC TV’s Gallery had a discussion on ‘Politics, Morals, and Morale,’… Sunday Telegraph’s Peregrine Worsthorne,… “that private moral slackness was an aspect of that insouciance which comes from a party’s being long in office, and perhaps could not be separated from a deeper, more dangerous slackness.’”

And presages of the “loneliness epidemic”.

An older novelist, Sid Chaplin…. after wryly defining ‘self-sufficiency’ as ‘the means to get out and away and return in time for a favourite television programme’, he wrote in the Guardian of how, ‘I have been struck in my wanderings this summer by degrees of social isolation; the aged sitting with their parcels on park benches; the holiday-makers sitting in cars, apart from each other as well as the folk of the countryside, who seem equally disinclined to fraternise. And Chaplin noted that ‘a couple of American poets who had walked the length and breadth of the United Kingdom told me that they were not impressed by our traditional English reticence. They thought it had gone to seed in a barren self-sufficiency.’ In short, her wondered: ‘Are we contracting out of community?’” (p. 247-8)

And does this remind you of the boosterism of so-called artificial intelligence?

Housing in Britain, a futuristic survey published by the Town and Country Planning Association. ‘A dream home for every family is on its way,’ declared the Evening New’s enthusiastic summary. ‘Millions of families within the next 40 years will have two homes and two cars. And the working week will be cut to only 24 hours - to produce the new leisured class.’ Two specific developments … apparently held the key to future domestic bliss. One, the more predictable, was ‘revolutionary labour-saving gadgets and equipment;… Rooms will vacuum-clean themselves, food will be prepared and housework done for them. All they do is flick a switch.’….The TCPA’s crystal ball could detect only one significant flaw. The breadwinner of the future is going to have to spend a greater proportion of his income on providing this luxury living.’ And accordingly, ‘he will be paying a bigger mortgage over a longer period, and putting down a smaller deposit.’ (pp. 431-2)

And as for politics - this is highly suggestive of a modern Twitter row:

“Speaking at Birmingham’s Bull Ring, Douglas-Home received the roughest of rides - not just non-stop heckling and gales of derisive laughter, but also right in front of him the unveiling of … a ‘cardboard monster’ with ‘the body of a pre-historic reptile and the face of Sir Alec’. (p. 501)

Other picks of the week

Listening

The History of England podcasts were what really got me into the genre, my discovery of them coinciding with a post-50, get-fit-now-or-never drive to regularly use the gym. (Since sadly derailed by Long Covid.) David Crowther is not a professional historian, just a man, as he says “in a shed”, wrapped up in this fascinating story. Now up to No 374 and still in the middle of the Civil War, it is also a long history, but easy to listen to. And most of us have strong and weak points in knowing our history; this is guaranteed to fill the gaps. (I’ve never really got into the War of the Roses.) It is, largely, traditional narrative history of politics and wars, although the members-only shedcasts get into some women’s history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Margaret Cavendish.

Thinking

British-Palestinian writer Selma Dabbagh on the London Review of Books blog sets out the reasons why the ruling by the International Court of Justice on Israel’s actions in Gaza is so important. It seems every time I give another speech, or make another intervention in the House, the death toll is 1,000 higher.

Researching

The relationship between humans and pets is - certainly in the UK - something that’s current at the centre of much debate: rising numbers of human injuries from dogs, worry about cats’ environmental impacts, animal refuges overflowing with Covid-era adoptions gone wrong. Taking the long view, researchers have been looking at how medieval dogs were “workers”, including one who became an, official, saintly martyr, and how their roles changed as society changed.

Almost the end

I hope you enjoyed this bonus mid-week edition. The next should be Sunday - topic to be decided! Let me know if there’s something you think I should write about.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

Very reminiscent of George Orwells The Road to Wigan Pier. There might be improvements in access to bathrooms but so many of the realities of the vast gulf between the North and Southern parts of the UK remain as stark as they ever were.