Change Everything No 45: How Lieutenant Cook's Endeavour nearly didn't make it home

The myth of Australia as terra nullius is negated. There was a law of the land already, and it saved the Europeans' lives

Events

Published this week was a Planet Possible podcast I recorded on biocides, planetary boundaries, holobionts, and of course Change Everything. Well worth a listen I think!

Coming up: on Wednesday night I’ll be in Lewes, talking 'Should We Be Thinking About Our Futures Differently?’ with climate health expert, Professor of Intensive Care Medicine at UCL, Hugh Montgomery: tickets here. And on Thursday evening, in Sheffield, talking about the future of our universities.

Had Cook stayed on the north side of the river, he’d never have made it home

The story of the white settler arrival in Australia is usually told in a totally one-sided way. And with perspectives that betray the blinding ignorance - and frequently wilful misunderstanding - by the invaders of the peoples they encountered. Lieutenant Cook and his men as they progressed up the east coat commented regularly on seeing smoke - which they rightly took as evidence of the presence of people - but failed to connect that to their presence. The peoples along the East Coast communicated with each other by smoke signal, so news of the arrival of this large strange craft preceeded its actual presence.

That one-sided telling has now been balanced by a brilliant book, Warra Warra Wai: How Indigenous Australians Discovered Captain Cook & What they tell about the Coming of the Ghost People, by Darren Rix and Craid Cormick. And it really does turn the telescope around, revealing both fascinating realities, and also the deep tragedies of the deliberate, genocidal damage done to cultures that had been continuously accumulating knowledge for tens of thousands of years.

Photo by Johan Mouchet on Unsplash

One of the standout moments, among many, is probably one of the most famous, when Cook’s ship the Endeavour hit the reef at Kulki (Cape Tribulation) on June 10. 1770, and was forced to beach for repairs. That was very nearly the end of the story, for the authors explain that they first briefly landed on north bank of the Whalumbal Birri (Endeavour River), the country of the Guugu Yimidhirr people, before shifting to the south bank. That latter was in “an area known as Waymburr, which was a place of ceremony and peace. A place where blood was never to be shed.” (p. 262) The other side of the river had no such injunctions, and so the story of these British invaders might well have ended there.

On the south bank, however, over the 48 days that Cook and his men as they - unknowingly - ran roughshod over many cultural traditions and displayed by local standards incredible rudeness and greed, the locals sought hard to find a peaceful way through. The worst incident was when the Guugu Yimidhirr were horrified that the Europeans had taken a dozen large sea turtles from the reef and strung them up in nets on their deck. “This was not the right time for hunting turtles and taking that many would leave a large impact on resources.” (p. 270) When the Guugu Yimidhirr tried to take some of the turtles, rightfully sharing in their terms, blood was shed on the sacred land, for in the row that followed, a local man was shot, although perhaps only lightly wounded, for he escaped.

“Now a quite remarkable thing happened. Even though the British had just broken one of the strictest taboos, in shedding blood on the land of Waymburr - and should have been punished for it, easily triggering a conflict that would have led to many deaths on both sides - cool heads actually prevailed. The little old man known as Yaparico came towards the British, calming the agitated warriors. Being the elder of this area, he walked out in front of the British with a broken spear, wiping sweat from his armpit and blowing it towards Cook. According to Gungu Yumidhirr law, marking Cook with his sweat would mean the spirits would believe he was one of them, and would look after him and keep him safe. Yaparico also called Cook ‘Towun’, which is something like ‘a friend’. Cook had the presence of mind to understand this symbol of peace and had his men hand back the spears they had confiscated. Both sides then sat on the ground and mutual respect was established. Reconciliation Rocks is today a monument to the first act of reconciliation in Australia between the British and First Nations peoples. But the bama point out that reconciliation had in fact been happening there for many thousands of years, as different groups came to the land known as Waymburr to settled disputes. This is a very important story for the Guugu Yimidhirr people, as it contributes to negating the myth of terra nullius. It demonstrates that there was a law of the land and how people should behave on the land. So this is a story that the Guugu Yimidhirr people would like all Australians to know.” (273-4)

I would like to think that every Australian school child is today being taught that story, established by careful examination of the Endeavour journsls from a local cultural perspective by the late Eric Deeral, a Gamay Warra clan leader of the Guuguu Yimidhirr and his friend and Cook enthusiasn John McDonald. But I’m afraid I doubt it.

What is striking is how much the Europeans were bumbling haplessly around the Continent, starting with the Endeavour’s first sighting of land - or not. For the cooordinates Cook gives for Point Hicks (named after the junior officer who first “sighted” it) are 20 kilometres out to sea, so they may have only seen a cloud bank. But as the authors note, there is stilll a plaque memorial on the land to the event (p. 17), when there are so few similar marks of Aboriginal history. For the local Gunaikurnai and Bidwell peoples, this is known as Tolywiarar or Munda Bubal. In their Dreaming, the landscape here was created by Djidjigan, the rainbow serpent (a subject I wrote about in No 41), while the sea was responsible for other elements, searching for a place to rest.

The authors highlight how much the whole voyage was an accident. Lieutant Cook, for that was what he was then, was the third choice commander for the voyage, and Australia was not even his target. After he opened his signed orders after the primary purpose of the mission, the observing of the transit of Venus at Tahiti, he was told to look for an imaginary southern Continent east of New Zealand (which of course does not exist). He did chart the whole of the New Zealand coastland, heavily aided by a Polynesian navigator, the Ra’iatean man Tupaia, who also went with the voyage right up the Australian coast. He tried regularly to be a translator, but found no compatibility between his and local languages.

The authors go to Lisa Fuller for an explanation of The Dreaming, a term coined in 1956 by the anthropologist W.E.H Stanner: “includes the Creation time of what has happened in the past, but also what is happening today and will happen in the future. ‘But all at once rather than as separate times. In the Creation time, the ancestral spiritis came and shaped the world - the hills, mountains, rivers, oceans, skies and stars - and created plants, animals and humans. They also created law, the rules by which we all live and behave. Spirit stories follow songlines all over the Country, the spirits marking the land as they moved.’ … It contains a vast cultural and legal framework, explaining the rules as to how people should behave, especially to the land. And the ancestor spritis that created the land can be felt though ceremony, song and artwork”. (p. 10)

This book is a lot more than an account of 1770 and where the Aboriginal people were then, however. For each of the peoples Cook and his men encountered, the authors follow through their later contacts with Europeans, horrendous accounts, inevitably, of massacres, of deliberate mass poisonings, of the wide-scale kidnapping of children and attempts to destroy their cultural and family ties, but also stories of hope - how Aboriginal peoples have survived, preserved what they can of their culture and knowledge, and are seeking increasingly to educate all about it.

And sometimes the land itself seems to be cooperating, as in the case of the Dharawal, who were fighting a development planned on their land, at a site called Sandon Point.

“The mob were protesting, saying it was a significant site, but the Land and Environment Court said it was not, as it was already being mined. Then Country spoke for itself. A big storm came through on top of a king tide, with the waves breaking over the lagoon there, and they uncovered the remains of a man in the sandhills. He was identified as being a Kuradji, a ‘clever man’, and over 6,000 years old. For perspective, that is twice as old as the ancient Egyptian pharoahs.” (p. 56)

It is from the Dharawal that the title of the book is drawn, from the Endeavour’s arrival in Botany Bay, where the ship’s artist Sydney Parkinson, said the local people shoulted “warra warra wai”, long translated as “go away.” “It is now known more accurately to mean ‘you’re all dead’ - a warning to others that they had encountered spirits of the dead.” (p. 65) For white was the colour of such spirits in the Aboriginal Dreaming.

There are few such direct records of the First Nations response to the Endeavour, but one fascinating one is from the Butchulla people on K’gara (which settlers called Fraser Island), a song that survives in the original language, and appears as follows in a translation from 1923

“These strangers, where are they going?

Where are they trying to steer;

They must be in that place, Breaksea spit, it is true.

See the smoke coming in from the sea.

These men must be burying themselves like the sand crabs.

They disappeared like the smoke.” (p. 162)

Another fascinating element that the book touches on, and which cries out for more explanation, if indeed enough material survives to allow it, is the many white settler people - mostly convicts and survivors of shipwreck - who lived with the First Nations, usually briefly, but sometimes for decades, and did not always want to return to their original culture. The book has fascinating and contrasting photos of the Frenchman Narcisse Pelletier, who spent 17 years with the Uutaalnganu people on Cape York from the age of 14, and James Morrill, who lived with the Juru and Bindal people in northern Queensland.

It also keeps returning, with sadness, to the frequent and awful depredations of the “native police”, men, usually young, some of them kidnapped into the force as mere children, who were turned against their own people, under the command of white officers. And the price for desertion, was often death, as with the case of two unnamed men who deserted from the command of the vicious John Jardine of Somerset, Queensland, a man who over a ten-month cattle drive from Rockhampton boasted of 80 notches on the stock of his rifle, representing First Peoples he had killed, and was then appointed police magistrate. (p. 286) With many of the records deliberately destroyed, this is another area crying out for more research.

But this book is ultimately hopeful, and in its own publication an indication of progress. Its aim, ultimately, is summed up in the words of one of its interviewees.

“The thing that Phil Rist [a Traditional Owner of the Nywaigi people, to the north of what is now Townsville] most wants Australians to know, after all the complexity of the past, is really quite simple: ‘It’s not about race, it’s about need. If we agree that this is the oldest living continuing culture in the world, so how do we protect that? In fact, that’s everybody’s responsibility, not just the blackfella.” (p. 229)

Picks of the week

Reading

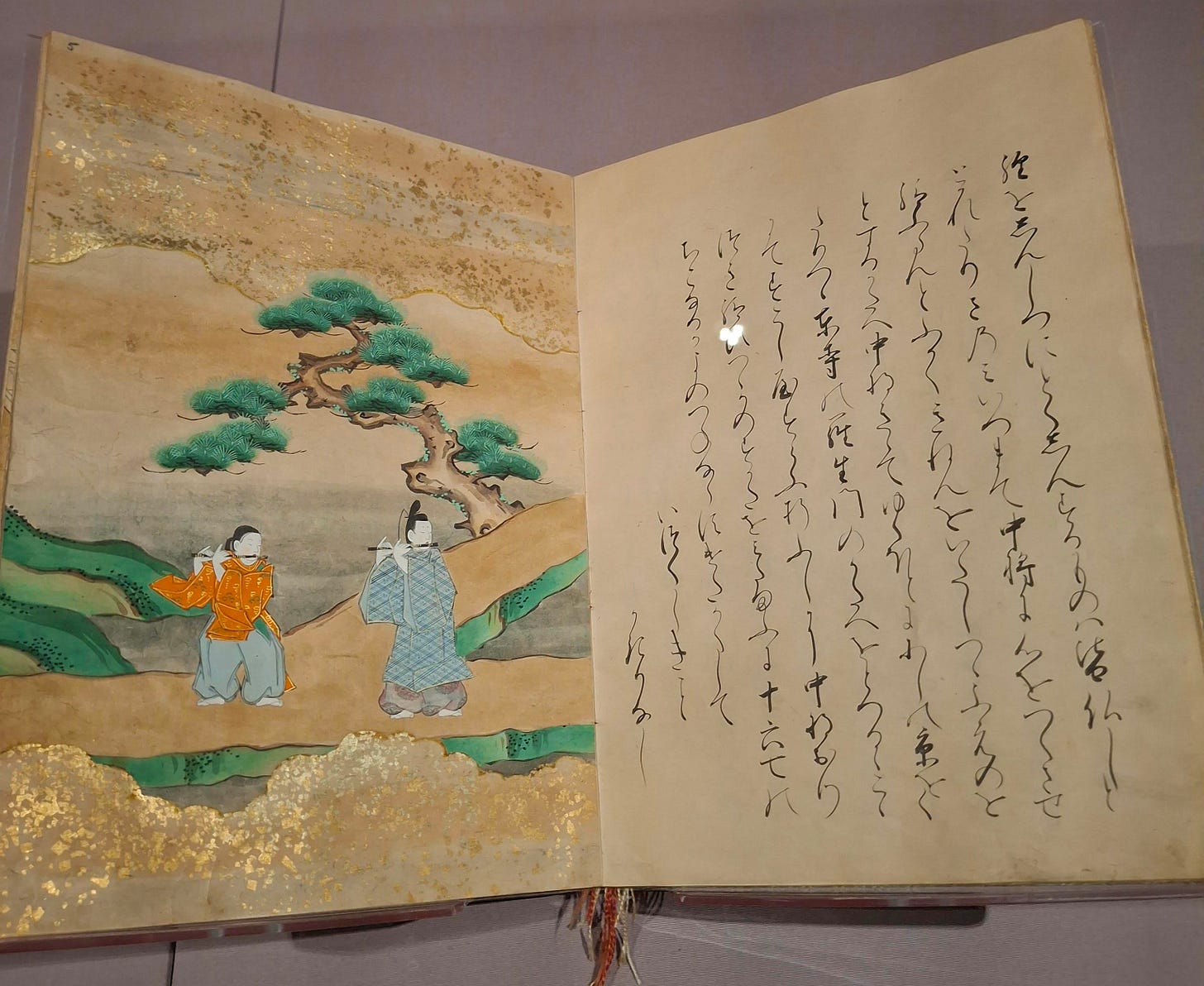

Popped into the British Library “Treasures” gallery yesterday, and found one more bit of evidence that yes, anonymous is usually a woman. A late 17th-century “Nara” picture book, The Flute With Green Leaves, tells the story of a courtier, Ariwara no Narihira (a 9th-century poet who was something of a Casanova of his day), who is sent by the Emperor to find the source of beautiful flute music, was written by Isome Tsuna. No more in London, but a little research tells me she was a “prolific artist, author, and editor… known for her calligraphy manuals for women”. Digging a bit deeper, I found that she was also the author of the three volume First Instructions on Women’s Letter Writing (1690), which includes 57 sample letters arranged by season.

Listening

The economist Dani Rodrik has claim, with writings from the start of the century, to having seen more clearly than most political chaos that would be created by globalisation under late neoliberal capitalism, with his thesis of the political trilema, that democracy, globalisation and national sovereignty are collectively incompatible, only two of the three can fit together (in varying combinations). On the Past Present Future podcast with David Runciman, he talks about where we are now, and offers the helpful thought that while technology, geopolitics and societies have changed enormously, politics (I would say particularly in the UK) seems to be frozen in a toxic stasis. He’s right, although with all the talk about “creating jobs” - in an ageing world with birth rates falling off a cliff - also not escaping tired 20th-century frames in other areas.

Thinking

I was pointed this week to a whole rich page of quality multimedia resources about trees, from the world wide wood, to tree activism, to trees in history: well worth checking out.

Researching

Empathy starts really early in human babies, as early as nine months, and is firmly established by 18 months, as found in a series of tests that (as happens all too rarely) combine Global North and South research. “An adult – either a local researcher or the infant’s mother – simulated pain or discomfort, saying “oooh” and “ouch” as if hurt while rubbing their finger. Then researchers observed the children’s facial expressions and whether they engaged in any comforting behaviors, such as stroking or hugging… It was found in both UK and Ugandan children at the same ages, despite differences in upbringing.” One for those who insist on stressing competitiveness and aggression as at the core of the human condition.

Almost the end

Can’t resist a suggestion to watch out for the rare oily-kneed beetle. That’s speaking as someone who was nicknamed “rusty joints” in primary school because of my creaky knees. Although for the beetles it is a defensive mechanism: they secrete “an oily yellow-orange substance from their knee joints when alarmed” - possibly something I could have used when I was aquiring that sobriquet from a boy who really didn’t like me.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.