Change Everything No 44: Famous, successful women - why have they been written out?

We need to escape the 20th-century thinking that could only see male, white history

Event news

In London, on Saturday, May 17, I'll be with Tony Juniper at a session of the new Fleet Street Festival titled Change the World, Save the Planet: A Hopeful Guide. You can book tickets now. (Special Substack treat, the code FOW50 should get you 50% off!)

And them I’m looking forward to joining Professor Hugh Montgomery in Lewes on May 21. Examining a question - should we be thinking about our futures differently? - to which my book Change Everything has a very clear answer! Booking now open.

And if you’d like to buy a copy of my book Change Everything, from the UK Hive has it in stock.

Women artists and writers are everywhere, and were truly famous

At the 1853 Paris salon, Rosa Bonheur exhibited a painting that many who know the Western art tradition may immediately recognise as a famous – and brilliant – work, as was recognised immediately, The Horse Fair. It is exhibited today in The Met in New York.

From a humble background, Bonheur went on to enjoy the patronage of aristocracy and royalty (including Queen Victoria), and was so financially successful that she was able to buy and comfortably live her life at the Chateau du Bly near Fountainbleu. At least three biographies were published during and soon after her life, and a book Women Painters of the World published in 1905 had her name in the subtitle as the temporal bookend, the other being Caterina of Bologna, the official patron saint of artists.

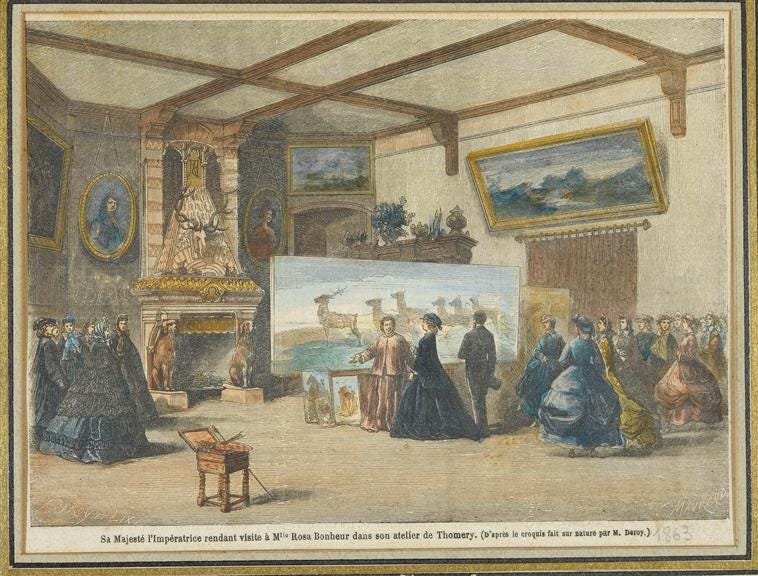

The French Empress visiting Bonheur’s studio. (Source)

Bonheur was in some ways a radical pioneer – she wore trousers for convenience when sketching at the actual market, which was technically illegal, but in other respects she did not – by gender – particularly stand out. As a modern scholar notes:

“From 1760 to 1830 more than 1,300 women exhibited more than 7,000 works of art in London’s and Paris’s premier exhibition venues. Like exhibiting male artists, they regularly sold their work, often for comparable prices, and were thus understood to be practicing art as professionals. Like men, they trained with men. Like men, they studied the nude figure. And like men, they were called geniuses.” (p. 70)

If we go further back in time, relying on one of the most monumental works of original scholarship I have ever read, Jane Stevenson, Women Latin Poets, who was able to find hundreds (and hint at thousands) of learned women in the Western tradition from the Roman Republic through to the 18th century. This only a decade after so distinguished a feminist historian as Gerda Lerner was saying there were no more than 300 learned women up until 1700 in the entire Christian era.

As the early modern era progresses, Stevenson puts together a fascinating account of the way cities and even countries came to regard the possession of an extensively educated woman scholar as a mark of pride, and someone to be paraded before important visitors, at which point they usually delivered a formal oration or similar. (So much for the theory that women were always supposed to remain silent.)

Frenchwoman Camille de Morel (1574-1611), was from a minor aristocratic family, whose mother held a humanist salon where her daughters works were often read, and part of a circle of similarly educated young women.

In this work she mourns her sister, celebrating her intellect:

Lucrece, why did you leave the earth alone,

To ascend into heaven, why did the fates give this to you without me?

You who were once the sweet solace of my sad mind,

My darling, and half of my soul …

Above all, dead sister, it is my grief to remember

You used to cultivate the sacred gifts of the divine Muses,

It is my grief to remember, since I lack you, my dear,

And what you are in your excellence, so swiftly snatched.

But it helps to remember, since a person who lived without sin

Lived long, and does not know how to die.” (p. 193)

One factor that led parents – usually fathers – to decide that educating a daughter in Latin – and other Greek, Hebrew and even more esoteric languages – was that it might be good not just for her but as a way of advancing the whole family. Often, but not always, such fathers were professional educators themselves. One such English character was Bathsua Makin, who wasn’t pulling up the drawbridge behind her, but instead advocated for the education of girls, with the text An Essay to Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen, and founded a girls’ school in Totttenham with a full academic curriculum.

Juliana/Julienne Morell (1593-1853) was writing letters to her Catallan father in Latin at age seven in Barcelona. He committed murder and they were forced to flee to Lyon, where she defended a Latin philosophical thesis in a public audience before Margaret of Austria at the age of about 14. Her father then removed her to Avignon, where he wanted her to study to become a doctor of law. However, she was determined to become a nun, and attracted the support of local nobles with another Latin public defence, and so was able to enter the convent of her choice. Her father refused to pay her dowry; the Pope eventually did so. But even there she didn’t escape, or chose to escape, speaking her various languages (which also included Greek and Hebrew) for distinguished visitors.

What is happening here? I am not claiming that the European past was some kind of feminist paradise, but that there was always space, sometimes big spaces, for women to occupy artistic and creative realms, often to be admired, become famous and celebrated, and – very occasionally – even quite wealthy as a result. This is something that feminist historians have over recent decades have been uncovering pretty well wherever they look.

Yes, sometimes the women creatives enjoyed privileged backgrounds, like Aemelia Lanyer, author of one of my favourite poems, the moderately well-known Ode to Cooke-ham, but often, like her contemporary, and definite contender for the first female professional writer in English, Isabella Whitney, who wishes she was rich enough to be in a debtors’ prison – since you needed assets and standing before anyone would lend you money, was not.

Yet still, in popular imagination, taking just the English language (since it has such a dominant place in the global sphere still), “famous writers” (and a great many syllabi) are likely to take you from Chaucer to Donne to Shakespeare to Milton to Keats and Wordsworth, to Bryon, to Dickens, to Kipling (really!!) to Orwell. (I did not have to put any first names in there: you know them.) See for example an India Today “World Poetry Day” commemoration from 2017. (Why they should be celebrating _English_ poets is a whole other question.)

That is a list unchanged from the twentieth century, yet we are now well into the 21st. I am not here making an argument for more modern writers – although one could certainly be very well made – but rather that we are accepting an extremely partial and biased twentieth-century view of what is the “great work” of the past. As so often, the thinking from that narrow period is gravely limiting our intellectual boundaries, and education, today.

Artists of minoritised communities have similarly found more of a place in the mainstream of creative endeavours than commonly credited today. Even if the compromises they had to, or chose to, make feel extremely uncomfortable. So Guillaume Lethière (1760–1832), the son of a formerly enslaved woman of color and a white government official and plantation owner trained in France as an artist, survived the dangers of the the Revolution to become a favorite artist of Napoleon’s brother, Lucien Bonaparte, and held positions at the Académie de France in Rome, Institut de France, and École des Beaux-Arts, while also being part of a Caribbean-linked community of high level professional friends in Paris. It was only in 2024 that an exhibition in the US and then Paris, and an accompanying book, brought him back to public attention. Below is his Judgement of Paris.

Picks of the week

Reading

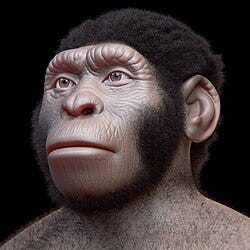

I have been a fan of paleoanthropologist John Hawks for more than 20 years, going back to my early blogging days. He’s famous - and in some quarters controversial - for being part of the Homo naledi excavation team, which in finding the remains of the relatively small-brained, hominin has stirred up a flood of scientific controversy in concluding that they buried their dead, and, maybe, made art. The team has been open and iterative in publishing its finding, and engaging with constructive critics, and John has just set out in a blog post the process and how they have been winning over some of the original doubters. A real model of how science can be done.

My next book engages with the issue of how small-brained hominins could engage in sophisticated behaviour, as also, certainly did Homo floriensis, the so-called hobbits. And how interesting it is that some people get very hot under the collar when it is suggested this is possible, find challenges to claims of human exceptionalism somehow personally threatening. But when you think about how are understanding of the sophistication of non-hominin animals is growing, surely this should be applied to our ancestors also?

If I had a time machine …! Source

Listening

Warning, distressing: I am going from caring hominin behaviour to genocidal human. The New Books Network interview with William Kiser, author of The Business of Killing Indians Scalp Warfare and the Violent Conquest of North America is hugely informative. My knowledge of American history is scant, but I won’t be hearing the word California again without thinking about the accounts in this podcast. The state government, unlike others, may never have actually offered a bounty for scalps, but killers (frequently taking scalps as trophies) were celebrated as heroes by the settler population.

(And got to mention the timeliest of New Books Network Podcasts, an interview with the author of Electing the Pope in Early Modern Italy, 1450-1700.)

Thinking

Heartbreaking, but important thinking about the massive damage we have done to elephants, reflecting also on the importance of learning to their future: protecting herd matriarchs, and older individuals more generally is crucial for groups’ survival. Herds that lose them “are less cohesive, may exhibit reduced fitness or calf survival, and respond inappropriately to threats and predators”. The authors note that cultural dynamics are crucial, something until very recently humans have been trying to deny even existed in animals. (Yes, that is quite a big bit of the next book also!)

Photo by Mylon Ollila on Unsplash

Researching

Mitochondria are endosymbionts, long ago independent organisms who threw in their lot with other bacteria and settled down to live within them, generating energy for their hosts and outsourcing other functions to those enveloping bodies. Lynn Margulis fought for that understanding - with cooperation as the foundation of life - and eventually genetic studies proved she was right. But there’s a new twist now: they can move between cells within (so far as we know at least) the same organism. The moves have been observed so far in yeasts, molluscs and rodents.

It’s not yet clear why mitochondria are so mobile. Some studies have hinted that cells donate their mitochondria to their neighbours during times of need. In cellular emergencies, newly arrived mitochondria might kick-start tissue repair, fire up the immune system or rescue distressed cells from death. Other research suggests that mitochondrial transfer can be a lethal weapon that cancer cells deploy to gain an advantage.

It is a reminder of how little we really understand about how our own and other bodies work. I has been much in my mind, and in my work in the House of Lords: how might this interact with the changes we are making with gene-editing to systems on which we are at the most basic level of understanding?

Almost the end

If you as seeking some political good news: in Australia, Clive Palmer, Trumpist mining tycoon, spent perhaps $60m for 1.85% of the vote in the federal election, only just outpolled the "Legalise Cannabis Australia" party, which spent essentially nothing.

And yes, English county council and related elections may look rather small on the world scale, but I’m celebrating from last week the eighth successive year of Green Party gains in council elections. We won 79 seats (while the governing Labour Party only won 98), and our Projected National Share of the vote was 11 percent (Labour 20 percent). But it is more clear than ever, that with Britain now well into the age of five-party politics, first-past-the-post elections are a recipe for chaos.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.