Change Everything No 42: A parasitical grand house in Gloucestershire

Slavery and empire enabled a very ordinary man to amass extraordinary wealth

Book news

Looking forward to talking “Climate Change for a Fairer World” with Tony Juniper at the new Fleet Street Festival of Words (London) on Saturday May 17, where you will also be able to buy Change Everything. Suspect these tickets might sell out quite fast!

Should you be heading to Newquay this spring/summer, don’t miss the wonderful, small but perfectly formed Clemo Books. Had a lovely #Change Everything event there on Friday night (pictured below).

How Barbados’s destruction was Gloucestershire’s gain

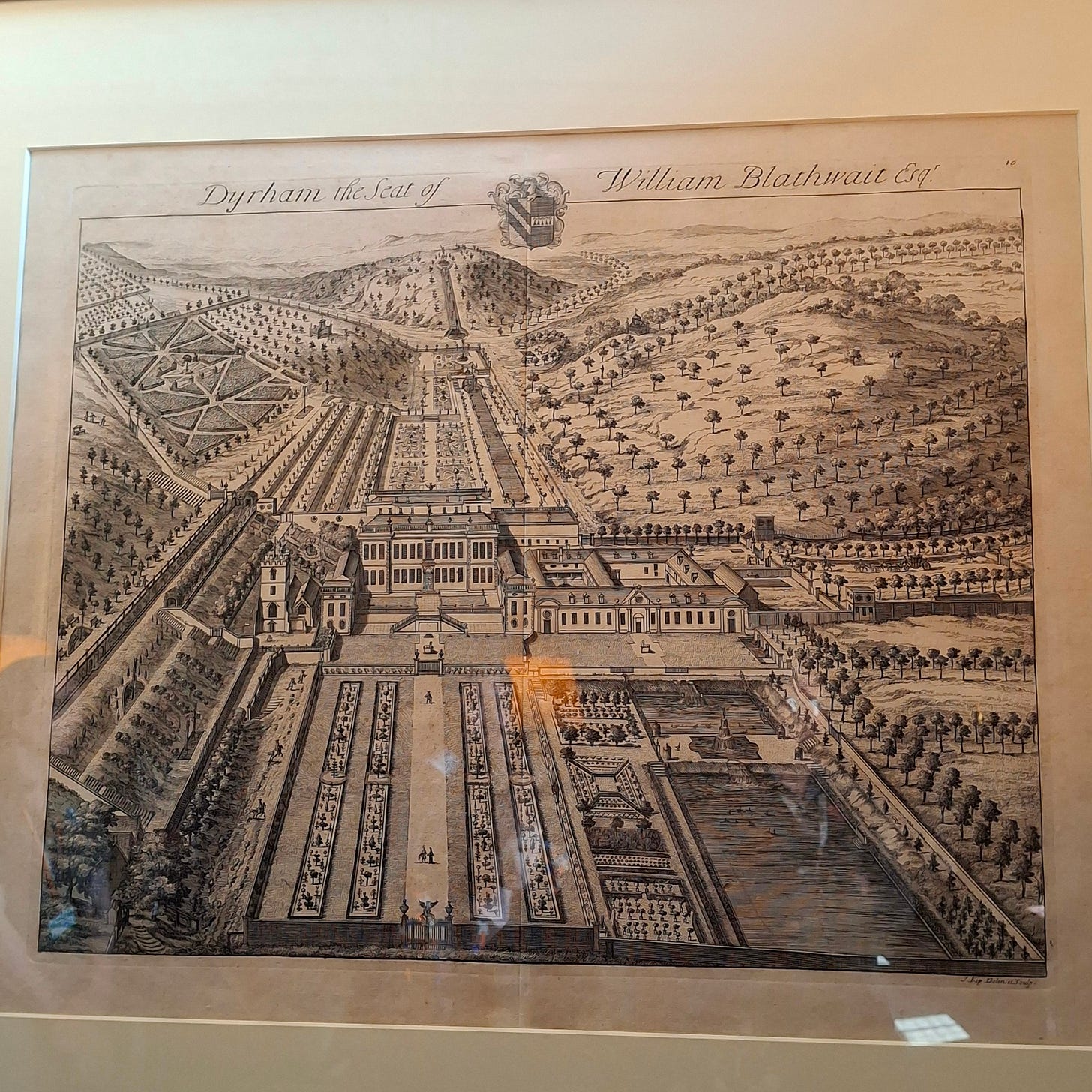

Last week I enjoyed, through the All Party Parliament Group on the National Trust, a visit to Dyrham House, just outside Bath. It is a house that fits at first glance fits the classic grand aristocratic model of many Trust properties, but on closer inspection lends itself to multiple narratives about colonialism and exploitation, and about UK’s always-tight enmeshing with continental Europe. Bringing those out - as the National Trust surely must - has got traditionalists hot under the collar, but anything else would be both an intellectual failure and a descent into Disney-style fantasy.

Reading around the story of its construction afterwards, one thing that was not perhaps brought out as much as it might have been was the relative modest origins - and indeed capacities - of its constructor. William Blathwayt’s father was a London lawyer whose practice collapsed during the Civil War, his mother came from a family of modest bureaucrats., As a modern writer notes: “A contemporary expressed surprise that the 'happy Possessor' of Dyrham bore no higher character than that of a private gentleman. Its size and splendour brought visitors flocking to the area to view the 'Magnificence of the Seat', the 'beautiful Irregularity' of the setting and the fountains and cascade, the finest in the country after Chatsworth.”

That’s the man himself, a portrait in the Great Hall, looking rather undistinguished in character. (Although this was not a great period for English portraiture in general, as the many “after Lely” portraits hung around this one indicate.)

On reviewer of a 1930s biography summarised his life: “William Blathwayt, Esquire, after Dr. Jacobsen has divested him of the last legendary veil, emerges as a glorified clerk, a flawless bureaucrat, and nothing more. He was a glutton for work, and neglected the duties of none of his numerous offices; he was exceptionally well-informed on the subject of the plantations, and regarded his colleagues on the Board of Trade as meddlesome amateurs; but, as the author assures us, he never originated even a new trick of office management, let alone a new policy, and his ideas were the conventional stock in trade of official mercantilism - and never altered by a hair's breadth.”

Yet this is what he was able to created, not just a grand house with artistic treasures (and a lot of what must have been frankly garish and hideous gold-coated embossed leather walls), but spectacular gardens, some of which the Trust has recently reconstructed. All this for the benefit of one man fulfilling multiple state posts; one article describes him as muddling through these roles.

The most spectacular artwork, pictured below, is "View of a Corridor" painted in 1662 by Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten, the quality and sophistication many orders of magnitude higher than the English portraits of the time. It is not hard to see how the sophisticated Dutch state was able to overtake the English one in chaos - for that is really what the so-called “Glorious Revolution” should be regarded as.

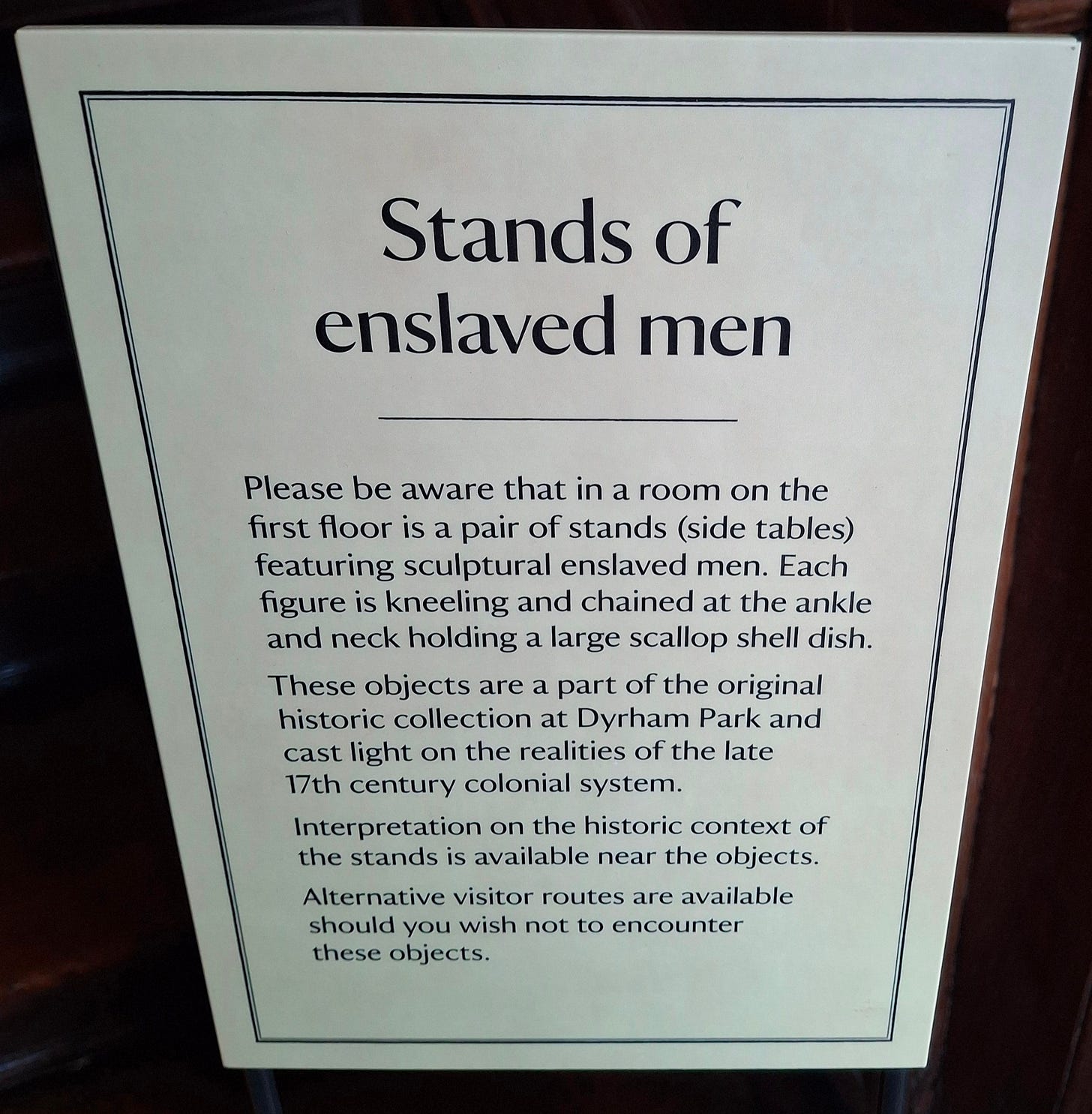

But Dutch and English skills combined with a reckless and arrogant attitude combined to vaccuum up large amounts of the world’s resources (and people) and bring them to the service of men like Blathwayt. The human cost is told (after much Trust soul-searching) in two statutes of enslaved men in chains, awful in their artistic banality, explained by the sign below.

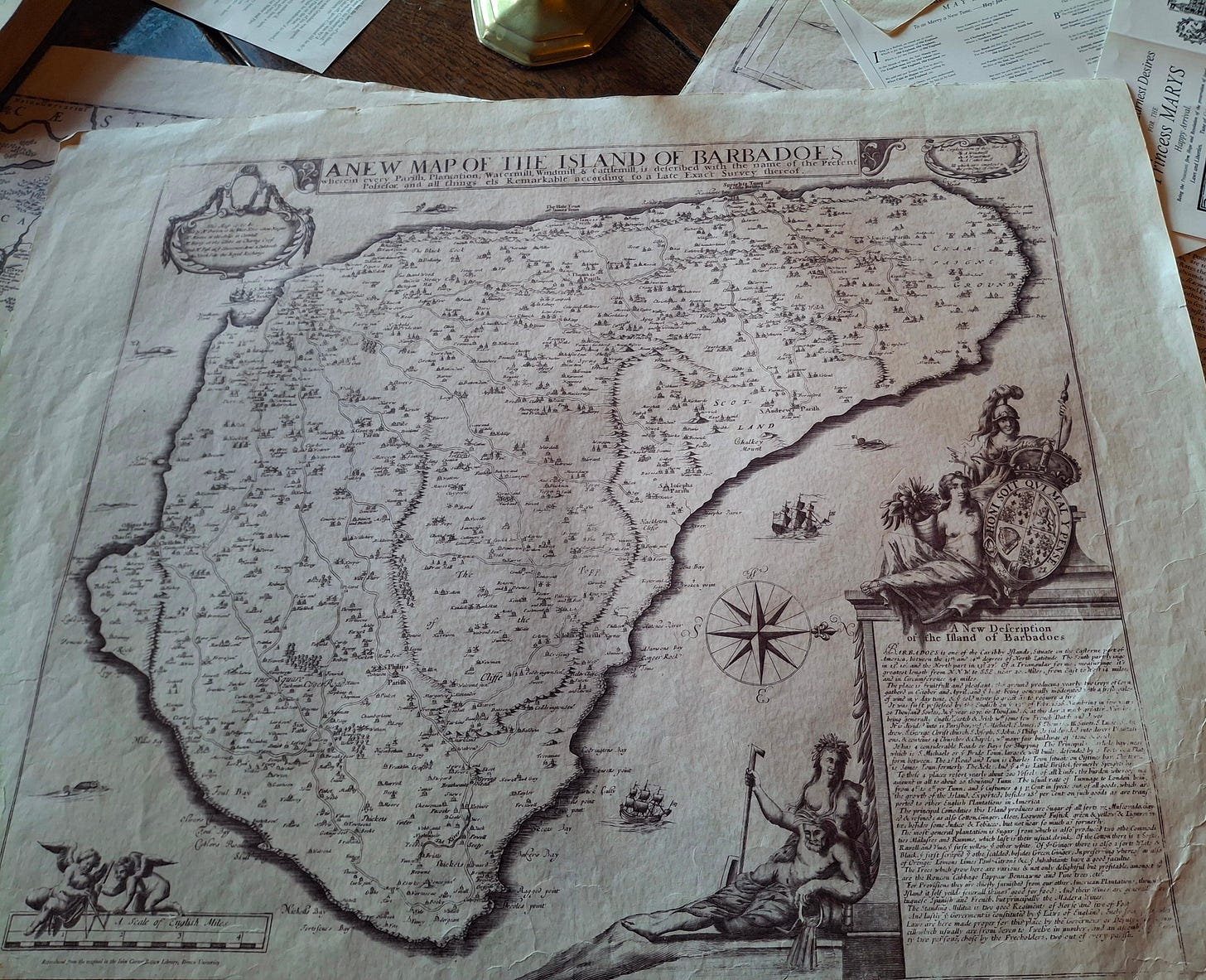

But it was a fascimile of a map of Barbardos, showing the island covered densely with plantations and farms, that really shows where the rampant wealth of Dyrham came from.

As an environmental history of the Caribbean explained:

“Barbados’s rapid conversion to a fully commercial sugar economy destroyed its forest cover within a generation.. sugar cultivation began in eanest in Barbados in the 1640s, and towards the end of the decade 40% of the island’s forests were gone; by the next decade, alarmed island authorities began restricting timber cutting; by then, it was too late. By the late 17th century, the island’s open landscape reverberated to the sound of turning windmills rather than burdsong… Soil erosion was such that one heavy downpour in 1668 carried hundreds of coffins from a local churchyard out to sea.”

Picks of the week

Reading

A reminder from Girt By Sea: Re-Imagining Australia’s Security of that nation’s frequently destructive colonial and neocolonial policies:

From 1976, with Indonesia’s formal annexation of Timor-Leste, “Over the next 15 years, a convenient quid pro quo emerged: Australia supported Indonesia’s continuing occupation of Timor-Leste, and Indonesia agreed to a joint development scheme with Australia in the Timor Gap. [Where new oil projects are still astonishingly in train.] The two states shelved their maritime dispute and split the profits from the Timor Gap evenly. In 1989, Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans and Indonesian foreign minister Ali Alatas infamously toasted to the formalisation of this arrangement in the Timor Gap Treaty while flying over the Timor Sea…. provides one example of Australia’s extractivist tendencies in its relationships with its Asian and Pacific neighbours - that is, its denial of their legitimate rights to self-determination to serve its own material and commercial interests, and in this case its strategic interest in maintaining good relations with Indonesia.”

The authors see similar in Papua New Guinea, particularly in light of the colonial administration’s role in approving the Panguna gold and copper mine in the Bouganville region, with major shareholder the infamous Rio Tinto. That led to grievances that results in an internal conflict from the late 1980s that lasted a decade and saw an estimated 20,000 people killed.” (p. 43)

Listening

Movement of people is a normal part of the human condition, if often not a voluntary one. This fascinating New Books Network podcast with Philip Harling, author of Managing Mobility The British Imperial State and Global Migration, 1840-1860, reports that more than 2.6 million emigrants left Britain in the 1850s alone. But it doesn’t just describe the policies and the mass flows, it also gets down into the individual stories, of South Asian indentured servants, abused on sugar plantations, fleeing to Venezuala, and the two men who escaped and turned up in London to protest, quietly shipped home rather than punished for fear of outcry.

Researching

You know that birds are often territorial. That wild cats and great apes are terrritorial. But newly hatched warty birch caterpillars, less than 2 millimetres long? Brilliant research shows how they hold - or under pressure decide to abandon - the desirable tip of a birch leaf with “multicomponent vibratory signals – buzz scrapes and drums”.

“When a conspecific neonate (intruder) is introduced to a leaf occupied by a resident, the resident increases its signalling rate up to four times that when undisturbed, and even more – up to 14 times – if the intruder enters the territory. Intruders rarely manage to take over the resident's defended space, with most confrontations (71%) ending in the resident maintaining control. Residents signal significantly more than intruders at all stages of the contest. If physical contact occurs, residents flee by dropping from the leaf by a silk thread.”

Nature truly is wondrous, amazingly creative, and so gloriously complex.

Thinking

A really must-read piece in the London Review of Books by the veteran British academic Perry Anderson starts from the fact that the term “regime change”, although subsequently co-opted to describe the usually US-led imposition of government change in Global South countries, was originally a term for describing a shift in the global politico-economic order, the last such having been the rise of neoliberalism. We’ve certainly not had this since 2007-8, he concludes:

“Taboo-breaking as the measures to master the crisis looked, and in good part were, judged by neoclassical canones what they essentially amounted to was a mathematical squaring,, or cubing, of the underlying dynamic of the neoliberal epoch, namely the continuous expansion of credit above any increase in production, in what the French call a fuite en avant, - a flight forward. So, once the measures required by its life-threatening emergency had stabilised the system, the logic of neoliberalism rolled forward again, in country after country.”

Where I disagree with Anderson is with his claim to a lack of alternative thinking. I have no disagreement that it is not to be found in mainstream economics. As he beautifully puts it “mathematisation had long anaesthetised much of the discipline of economics against original thought of any kind”. But it is green thinking - profoundly different to what came before in its understanding of ourselves as human animals entirely dependent on complex, creative but now fragile natural systems - that a new approach is to be found. And, drawing on indigenous thinking, an understanding that the future must be built from the ground up, different in different places according to their own character and life, rather than one unified system imposed from above. As I was saying in Newquay last week, whatever you ask me to talk about, local genuine democracy will always be at the heart of my answers.

Almost the end

The Guardian held a vote for its invertebrate of the year. And a tardigrade won. Of course! I got tardigrades mentioned in Hansard for the first time in my maiden speech in the House of Lords: still rather pleased about that!

What did you think?

You can also find me on BlueSky, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

Those who either inherited or made wealth are always parasitic, benefitting from the work of others and hoarding resources, taking the best for themselves. The slavery aspect is horrific but continues today in the UK in the form of domestic slavery and trafficking. The land grab by the aristocracy (combined with Enclosure Acts) is the one of the biggest resource thefts in our history. It should be reversed - even NT land is often behind a payroll, and limits access. We need state-owned land with access rights for all.