Change Everything No 38: International Women's Day - making sure women's contributions are not lost from memory

A focus on Bulgaria and Zambia - and very patriarchal America - exposes a much broader picture

Book news

Looking forward to being at the wonderful Clemo Books in Newquay, 7pm April 4, talking Change Everything. And I will be in Lewes for a book event on the evening of May 23, details TBA.

America the laggard as the Second World led

My involvement with the United Nations women’s processes started in 1995, when the twentieth anniversary of the 1975 first UN World Conference on Women was celebrated in Beijing. As a volunteer at the National Commission on Women’s Affairs I wrote the opening speech for Thailand’s representative. (It was, if I say so myself, quite a good speech, built around a Thai woman’s poem with the metaphor of escaping from the “dark side of the mountain” to the side of light. Unfortunately the minister did not actually speak English, so it was delivered from a text phoenetically written in Thai script. And was, I am told, consequently wholly incomprehensible. But I hope it is in the records somewhere.)

What I was unaware of them, and until reading this weekend, to mark International Women’s Day, Kristen Ghodsee’s brilliant and important Second World Second Sex: Socialist Women’s Activism and Global Solidarity during the Cold War remained unaware of, was how much women from the “Second World”, what the socialist bloc was known as, in alliance with socialist-leaning but non-aligned countries, contributed to the advances of the 1975 Mexico City conference that marked the starting point of the UN Decade For Women, and the assertion, against powerful opposition particularly from the United States of America, of a role for women outside the home. (She also wrote for Le Monde Diplomatique on these issues, and an academic open access journal article here.) Her focus is on Bulgaria and Zambia - refreshing to see the move beyond the obvious suspects.

That most of the women were operating within the framework of state women’s organisations has traditionally been used to discredit them. But when the state is granting women full legal equality, doing its best to promote education and professional training for women and encouraging full labour force participation, while in the USA calling for anything beyond a place as a domestic homemaker was likely to get you labelled a “communist” (“the prevalent discourse asserted that only communists would want to destabilize the naturally monogamous, nuclear, and patriarchal family in order to give women equality with men”), that is not such a terrible place to start. And of course you can always use the system for your own purposes.

Ghodsee sets out the shape of women’s activities in the international arena:

“While they never achieved everything they claimed, socialist countries (in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia) did make real strides in women’s rights before the Western democracies and their allies in the developing world. The policies and programs put in place were implemented by the state, but they were often shaped by women working within that state, women empowered at different times and in different ways. Their state-centric approach to women’s issues was promoted throughout the Global South through solidarity exchanges promoted by mass women’s organizations. Yes, these exchanges often supported Eastern bloc foreign policy goals in Africa, Asia and Latin America, but they also empowered leftist women as agents of social change and forced local male elites to make space for women’s organizing. Third World leaders who wanted military, technical or financial assistance from the Eastern Bloc had to at least pretend to care about women’s issues, and when compared with countries at similar levels of economic development, the state-centric approach provided ample empirical evidence that socialism challenged sexual inequality in traditional patriarchal societies.” (pp. 16-17)

She makes a powerful case that apparently autonomous women’s organisations - traditionally held up as the ideal model based on Western case studies, also have constraints on their activities. “A significant disjuncture might exist between what state socialist women’s committees did and what they said they were doing when they explained their actions to male colleagues… In much the same way that the now independent feminist NGOs frame their programs around donors’ priorities, state women’s organizations had to negotiate the political constraints of their various one-party states…. Many socialist women framed their activism in terms that might make them seem subservient to the male party elite.” (p. 52)

There is, for anyone who looks, plentiful evidence of the way in which women activists in these state systems could also be working to subvert misogynist aspects of them and the traditions of their societies. One can only call brave one effort by the Bulgarian Committee of the Bulgarian Women’s Movement (CBWN) to get men involved in childcare by suggesting apartment blocks be designed with a pub on the first floor beside an indoor playground, so men could watch the children, and their grandmothers, a break from childcare. Perhaps predictably, it failed to take off.

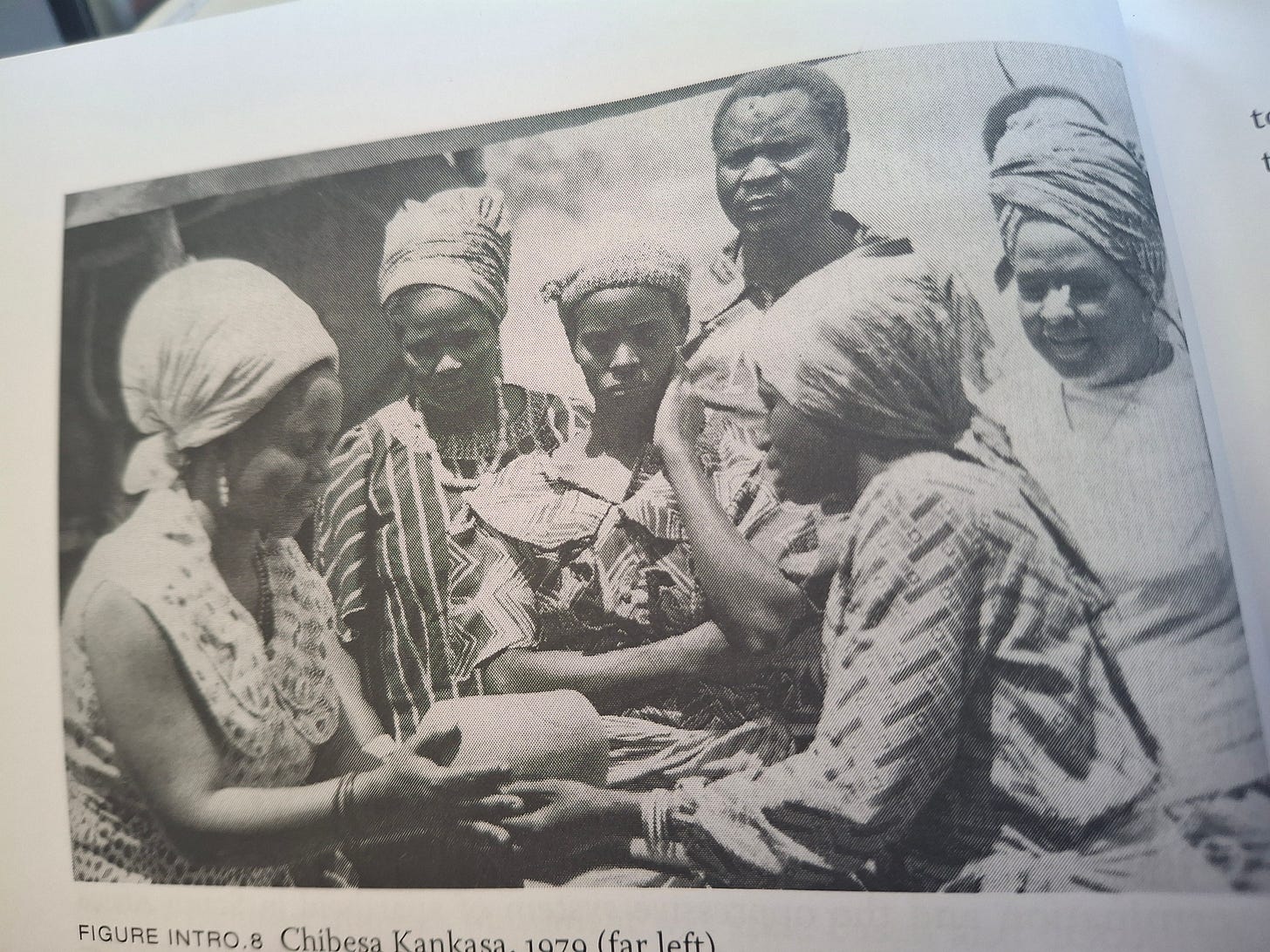

Global South women’s groups worked with the Eastern Bloc, but did not slavishly mimic them, adapting both UN and allies’ approaches for their own circumstances. The book extensively covers the work of Chibesa Kanska, who soon after Mexico City put together a group of Lusaka-based colleagues to serve on a committee to create a Zambian program of action. “The majority of the Zambian Program for Action focused on development… two chapters devoted to equality and only one chapter to discuss peace… a careful reading reveals both the similarities and the differences between the Zambian feminists and the Eastern bloc socialists. … paid maternity leave featured prominently in the section on employment, with the Women’s Council of Zambia arguing that ‘the nation should appreciate that having babies is part and parcel of national duty’ and women should not be ‘victimized for having babies’. The suggested solution however deviated from East European practice in that the Zambians believed that only married women should be eligible for maternity benefits.” (pp. 168-8)

It might all sound a bit quaint now, but women-to-women contact was important, and empowering. One of the most prominent women internationally was Elena Lagadinova, who had been an 11-year-old anti-Nazi partisan who after the war got a doctorate in biology in the Society Union, and worked as an agricultural geneticist, creating a more robust winter wheat variety that won her a national honour, spending two decades as the chair of the women’s committee

“The Committee of Bulgarian Women dealt mostly with international issues between 1950 and 1968… nurtured bilateral contacts with women’s organizations in the developing world. For instance, one stenographic protocol from a meeting of the CBW held on March 17, 1965, demonstrates that Bulgarian women were in close contact with key women leaders in Mali. The protocol shows the Committee discussing the material to be sent to Mali in response to a letter from Aoua Keita, a radical African woman who was an active militant in the African Democratic Assembly, which was fighting for independence in all of the French African colonies… agreed to spend 1,000 levs for pencils, notebooks, typewriters, printing machines, and other supplies for Mali in support of the women’s movement there. The CBW recognised that Keita was one of the most important women in Africa and hoped to invite her to Bulgaria.” (pp. 62-63)

From the perspective of this book, again and again the USA is a blocker, a laggard. When it did decide to pay attention to women’s issues in Africa, as evidenced by a report of 1961, it was fairly noted that women did most of the hard labour, but while making a moral case for their education, G. Mennen Williams also argued that “it might assist in the creation of market economies.” (p. 124)

Ten years on from Mexico City, the US under Reagan was equally obstructive. (And doesn’t this all sound so familiar?

“The Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women is sprinkled with asterisks noting the specific disagreements of a United States intent on defending its economic interests…. Paragraph 94 specifically targets the ‘coercive measures of an economic, political and other nature that are promoted and adopted by certain developed States and are directed towards exerting pressure on developing countries, with the aim of preventing them from exercising their sovereign rights and of obtaining from them advantages of all kinds”. The United States ‘reserved its position on paragraph 95 because it did not agree with the listing of those obstacles categorized as being major impediments to the advancement of women. These obstacles were ‘imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism , represssionism, partheid and all other forms of manifestations of foreign occupation, domination and hegemony, and the growing gap between the levels of economic development of developed and developing countries…. By voting against paragraph 259, the United States resisted the overwhelming international call to impose sanctions on the South African apartheid regime and to support the independence struggles in Namibia and Angola, a position trhat antagonized many African women attending the conference. Similarly, the United States voted against the paragraph on ‘Palestinian Women and Children’ because of its ‘strong objection to the introduction of tendentious and unnecessary elements into the Forward-Looking Strategies document which have only a nominal connection to the unique concerns of women.” (pp. 209-210)

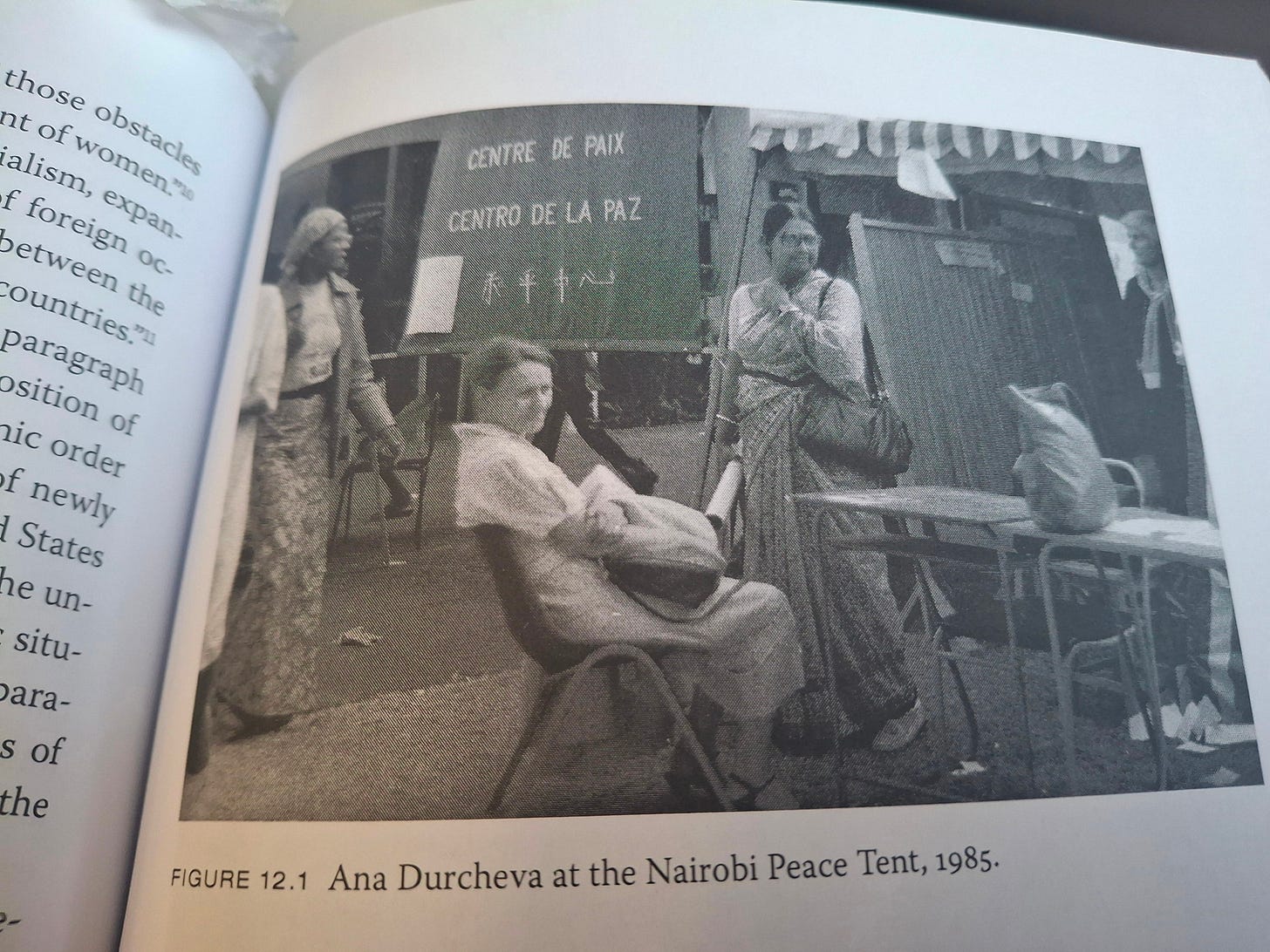

One account from the whole book might sum up why texts like this are so important. The author is speaking to Ana Durcheva, a Bulgarian activist who dies right in the middle of their conversation, as she is living in debt, with great fear of becoming homeless. Kristen attends her funeral. Ana wants to make sure a South African anti-apartheid campaigner who worked with the WIDF is remembered.

“During the chaos of the 1990s in Bulgaria, the banking collapses the rapid privatisation and dismanting of the welfare state, and the shrinking employment opportunities for middle-aged women like Ana, she took comfort that Ruth [Maputi] lived in a country where blacks and whites were finally equal. In her own small way, she felt that she had had a hand in that change, if only as a colleague and confidante of Ruth. “But sometime around 2005-2006, before the crtisis, I met an old colleague of ours from Berlin,” Ana told me. “I asked if she had an addressw for Ruth, because I wanted to send a letter. This colleague told me that Ruth had died and that she had been very poor and barely able to survive after 1990. She died living alone in some small village, completely disregarded by all those new politicians in the ANC.”…. No one was more ideologically committed than dear Ruth. Can you imagine your whole life given to the cause, only to be completely forgotten by those enjoying the fruits of the new world you helped to create?” (p. 227-8)

Recording, talking about, celebrating women’s history is so important.

Picks of the week

Reading

The marketisation of our universities around the world has a lot of answer for, in the damage done to people, and the quality of learning. And much more to come, sadly. The UK Office for Students says each university is "making perfectly rational commercial decisions about its financial model" but that risks leaving large areas of the country where whole subject areas and disciplines are unavailable. That the decisions are “commercial” is the problem in a nutshell.

Just one case study from Times Education Supplement

Listening

A New Books Network podcast with Chelsea Berry, author of Poisoned Relations Healing, Power, and Contested Knowledge in the Atlantic World, looks at how, by the time they came into contact in the 15th-century, Europeans considered poison a gendered “weapon of the weak” while Africans viewed it as an abuse by the powerful. Though distinct, both idioms centred on fraught power relationships. When translated to the slave societies of the Americas, these understandings sometimes clashed in conflicting interpretations of alleged poisoning events. I was listening to it just after reading some disturbing Far Right vaccine-sceptic material again, and the continuity of distrust between then and now struck me as something that would be interesting to explore.

Thinking

I know a poet or two, and have been enjoying a different perspective on them from an article in The Baffler magazine: “positions poetry as a vital site of innovation and experimentation, where language is continually renewed through its collisions with new media technologies, ultimately transforming not only the impact of these technologies on society but the very enterprise of meaning-making itself”. It is important not to have a one-dimensional view of the impact of social media.

More than words. Photo by Trust "Tru" Katsande on Unsplash

Researching

Researchers are - slowly - starting to pin down a little more detail about the links between the gut microbiota and the brain, such as this study which found microbiota composition is associated with changes in psychological functioning. It identified associations between functional domains—negative valence, social processes, cognitive systems, and arousal/regulatory systems—and the varied abundance of eight microbial genera in the gut. Although it comes with important caveats: how quickly the gut composition can change, which the authors note, and, my note, based on a study I saw reported this year, there’s huge ranges of results in studies of gut micrbiota between different labs. Something to think about next time you see an advert promising to check your microbiome for a fee.

E. coli - can be cuddly. Photo by CDC on Unsplash

Almost the end

Enormous respect - and very best wishes - to the women’s movement in Ukraine resisting Russian occupation through symbolic acts of defiance. I very much hope when the time comes they will have a prominent place in rebuilding the war-battered society.

And you can always trust the Germans to come up with a great compound word: Tesla-Scham is the word for the embarrassment of owning one of Elon Musk’s vehicles.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.