Change Everything No 35: A regime is not a country

In a distant corner of China, an author lives in a globalised countercultural frame that you will not find in Beijing

Book news

Somehow I’ve only just caught up with this lovely review of Change Everything, the book, by Stuart Aken on Medium. “I’d like to have all our current, and potential, politicians made to sit down and read this manual for a fairer and more workable world.” (‘ll definitely take that. Thanks Stuart!)

And publisher Ubound currently has a 30% Christmas discount - just £4.19 for the Change Everything ebook.

Don’t mix up a people and their government

A government is not a country, or its people. That is why I always try – if perhaps imperfectly – to speak about the Israeli government, the Iranian regime or the Burmese junta, rather than just the name of the country. As I reflected in the House of Lords on the brave resistance of Iranian women, as I frequently try to highlight the hugely courageous resistance to President Putin in Russia, every country has, in different ways and forms, resistance to dictatorial, repressive, discriminatory regimes. As in women’s resistance in the face of the horrors of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

And those people can be – in the long run always are – the way in which despotic regimes are toppled, often to the great surprise of the outside world. See Syria this weekend. I’m thinking of the many people I interacted with on my visit there in 1999, and hoping they might now be able to look forward to some stability, particularly in one of my favourite cities, Aleppo (some pictures here).

Only one side of China. Photo by zibik on Unsplash

I was reminded of this reality when reading Alec Ash’s The Mountains Are High: A Year of Escape and Discovery in Rural China, recording the author’s life in Dali, a rural valley in Yunnan province. It tempted me from the new book shelves of the London Library because it immediately made me think of Yangshuo, an area of Southern China I visited in the early 1990s, a beautiful area of limestone hills and sinuous rivers that was then a weird backpacker haven in a nation still barely opened to tourism.

China still had two currencies, Foreign Exchange Certificates and renminbi (people’s money). FECs had the same face value, but in exchange were about 40 per cent more valuable, so foreigners, only supposed to use the former, were always paying more. In the rest of the country, you exchanged your notes furtively down back alleys. A tour guide lectured me when I went to pay a bill in renminbi, “you must always get your change in FECs”.

But in Yangshuo, little old ladies stood on the corners chanting at every passing foreigner “postcards, change money, postcards, change money”. Even humble cafes had English-language menus, include that ubiquitous backpacker staple banana pancakes. And suffering the almost inevitable winter affliction of acute bronchitis, I got to see a traditional medicine doctor there who spoke enough English to prescribe for me the most amazingly effective cough medicine I’ve ever taken. At that stage I didn’t care that the ingredient list on the back included “snake bile”.

Modern Dali has gone further than that, however, sounding as a hippy-heading-towards-yuppie haven very like Nimbin in Australia. Yoga teachers and Buddhist temples rub shoulders with home-educating herbalists and refugee political activists, while the Chinese state leaves them pretty well alone. Ash explains:

“If there was a guiding mantra to Dali life, it was ‘natural living’… in the idiom of shumquiran to ‘abide with nature’. (Or in Dalifornian, to ‘go with the flow’.) In short: to let the natural state of affairs be, and live without excessive ambition or grasping for material possessions or success. This post-materialism – born of disillusionment with the capitalist nation that China had become – was for some rooted in socialist utopian ideals. Some ever harked back to China’s early Community era, ignoring the horrors of the Mao years to wax nostalgic about a time when everyone was equal and communal mission meant more than personal wealth. For others, the underpinning went further back still, to ancient Chinese philosophy. … for most in Dali, Taoism was simply a philosophy of life to which they subscribed. Many kept a well-thumbed copy of Zhuangzi’s teachings on their bedside table: an itinerant Taoist sage of the 4th century BC whose irreverent collection of anecdotes Wandering on the Way began with a chapter on ‘Free and Easy Wandering’. (pp. 62-3)

This is in a natural and in many respects social environment pretty closely resembling the Shangri-la of James Hilton’s bestselling 1933 novel Lost Horizon, set in Tibet, where a plane containing four Westerners crashing while fleeing a war-torn Afghanistan. Fascinatingly, the Orientalised myth has a genuine Chinese origin, Ash tells us, a 5th-century poem known as Peach Blossom Spring, in which a man accidentally finds a hidden valley where there are peach trees, plentiful crops, fresh water and stunning scenery, inhabited by people who fled the tyranny of China’s first emperor. But it was probably more directly inspired by articles in National Geographic by a botanist, Joseph Rock, from Lijiang, near Dali. (p. 17-19)

Although this is the 2020s. So one couple Ash describes, from refugees from industrial heartland Shenzhen, “stayed in solitary confinement in their cowshed, playing video games on an enormous screen that took up the entire space. Frankie was a League of Legends champion, and earned money by live-streaming his campaigns, while his girlfriend dropped acid and painted psychedelic self-portraits with spiders crawling out of her face.” (p. 23)

Ash’s book is a – by genre – very familiar. The debt to Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence is obvious. Yet what makes this stand out is that this is a side of China about which we so rarely hear, depicting behaviour that feels so familiar. One couple Ash talks to explain they moved out of what we’d call the rat race for the sake of their daughter.

“They didn’t want her to go to a state-run school any more, or to grow up in the city. When she had started primary school back in Shanxi, they had been horrified to discover that from Grade One she was already being prepped for standardised exams. ‘They want to create children who are all the same,’ he mother said…’We chose a natural education so her own true nature is not obliterated, so she can understand what she likes and who she really is.’ … Guogou was now in a Walford school in the township near Silver Bridge Village, set up specifically for migrant families. And she couldn’t be happier.” (p. 59)

There is evidence for globalisation working in many ways.

It was no surprise that the city transplants of Dali had a strong environmentalist streak. Almost everyone I met tended their own vegetable patch, and was passionate about organic crops or ecological protection in general. Several mentioned the 1962 book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson to me, a tract against the use of pesticides. Others cited the Russian book Anastasia, a memoir about finding an alternative, natural way of life on the Siberian taiga, as their inspiration for moving to Dali. The British agrarian John Seymour’s The Complete Book of Sel-fSufficiency, published in the 1970s, was also popular.” (p. 134-5)

But of course the Chinese state is inescapable, and, even if operating with broadly good intentions, deeply destructive. Ash talks about how after President Xi’s visit to Dali, when he saw an algae bloom on Lake Er and said from the village: “You must protect Erhai well,” reflecting an official slogan “Clear waters and green mountains are mountains of gold and silver.” Inn and business, and houses, around the lake were cleared out, 1,000 families displaced, “sewage police” descended on nearby villages, and the lake, as Ash puts it “terraformed”. And the whole are was gentrified. New businesses moved in. (pp. 201-3)

Picks of the week

Reading

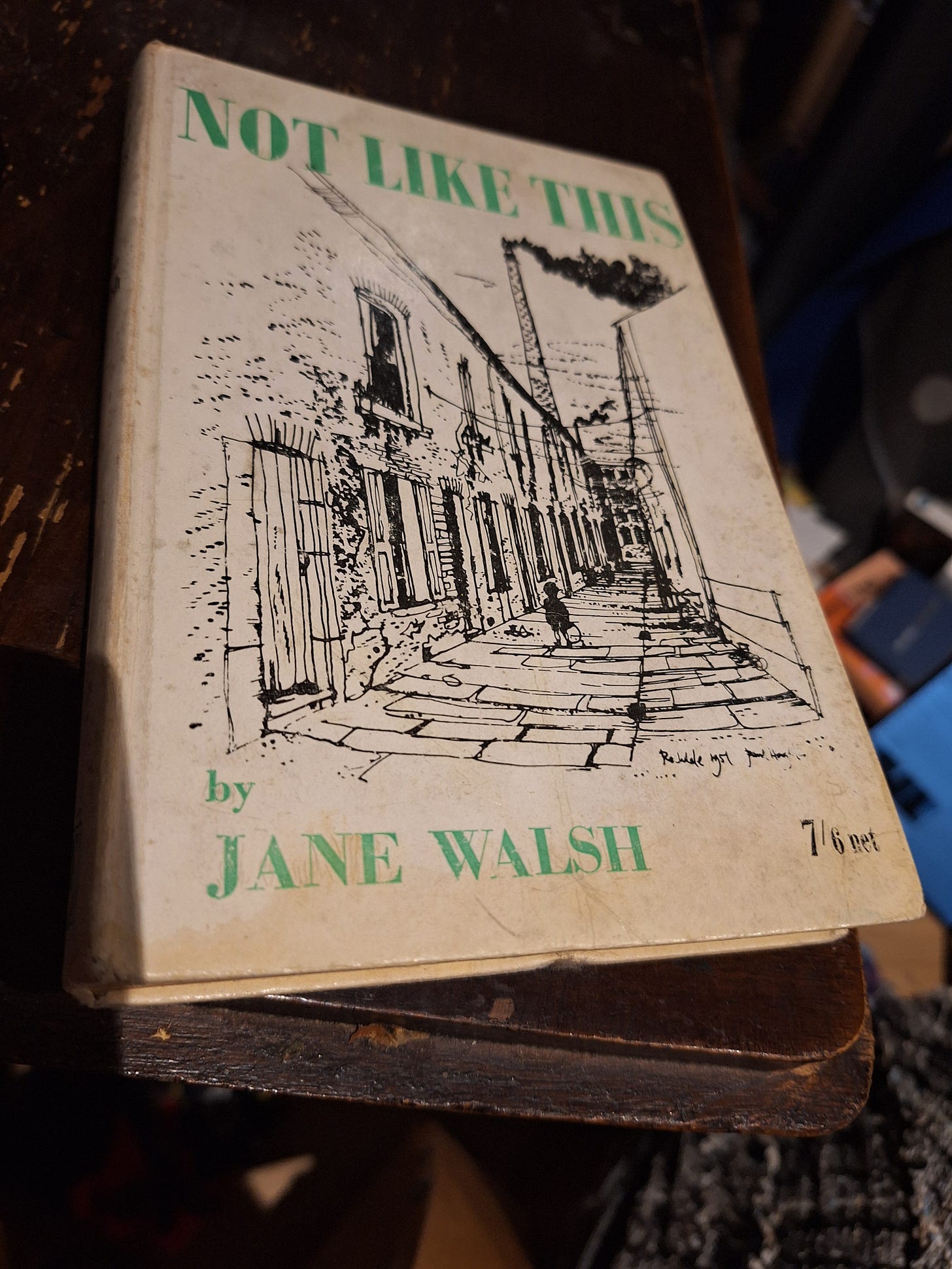

One day - lots of my suggestions for things to do start like that - I’d like to become a regular contributor to expand the women’s history offerings on Wikipedia. One day. But in the meantime, just occasionally I throw something up, as I did for the writer Jane Walsh way back in 2011. Not heard of her? I’m not surprised, but her vivid, powerful account of life in Oldham in desperate poverty was published by the very mainstream Lawrence and Wishart in 1953, and reviewed by the New Statesman. I wrote about it - with extracts. If you’re in publishing, this is a book crying out for a new edition!

Listening

I’ve forgotten now who recommended The HPS Podcast: Conversations from History, Philosophy and Social Studies of Science on BlueSky (you can find me on the fast-expanding social site here), but it is one of the best podcasts I’ve encountered. (And if you read this Substack regularly, you’ll know I’ve got quite a collection.)

Not just because it has some of my favourite scholars, from Donna Haraway to Cordelia Fine. (I recently revisited her brilliant Delusions of Gender for Resurgence Magazine.) I binge-listened to the first series - they’re up to four now, so plenty more to come - and was particularly taken by Rachael Brown on the downfall of the value-free ideal in science, and Kristian Camilleri on the disunity of science: is there such a unitary thing anyway? So much we need to unpick about 20th-century verities that have hung on in popular understanding long past their rightful time.

Photo by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash

Thinking

Government austerity - the slashing of services and social supports - has negative impacts on human health and wellbeing. That might seem to be a statement of the obvious - certainly the experience of the past 14 years in the UK - but comparative statistics show this is an international experience, mirroring The Spirit Level’s study of inequality. Researchers conclude: “If mortality rates are to be improved, it is essential that the Labour government in the UK, and other governments around the world, understand the evidence, quickly reverse the erosion of public services and social security systems and protect those at greatest risk.” Yes!

We should not rest until the last food bank closes because of lack of demand. Photo by Melanie Lim on Unsplash

Researching

One more reminder from the field of antimicrobial resistance of how little we understand about the immensely complex microbial world - which has after all collectively been on this planet for some 3.4 billion years, in which time they’ve learnt a thing or two. A study reports that the massively studied E. coli bacteria have an “entirely new [to our understanding] survival strategy”. "E. coli is altering its molecular structures with remarkable precision and in real time. It's a stealthy and subtle way of dodging drugs”, alternating its ribosomes just enough to prevent an antibiotic binding on the sites that it is designed to attach to. What other mechanisms do they have? “Bacteria are known to develop antibiotic resistance in different ways, including mutations in their DNA. Another common mechanism is their ability to actively pump and transport antibiotics out of the cell, reducing the concentration of the drug inside the cell to levels that are no longer harmful.”

E. coli - smart critters: Photo by CDC on Unsplash

Almost the end

Got to share this lovely tale about a Dutch intentional community where residents need to devote at least half of their land to growing food. But beyond that, it is a largely a case of self-government: “Residents can build houses however they like, and must collaborate with others to figure out things such as street names, waste management, roads, and even schools.” And it has a growing waiting list for residency.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

What a ride, thank you, I will dig up Alec Ash’s book! It reminded me of Dan Wang’s 2022 yearly letter about Yunnan: https://danwang.co/2022-letter/