Change Everything No 27: 'One Health', a systemic way to think about the state of the planet

How a deadly disease in bats leads to more human baby deaths. But not directly

Book news

Enjoyed a brilliant session at Green Party conference (and afterwards signed a lot of copies of Change Everything!) with Caroline Lucas, talking about her just-out book Another England is Possible, and Danny Sriskandarajah with his Power to the People. We need to write books, and use many other media, to tell stories about how the future can work out, how democracy, change and hope can be delivered. Day-to-day politics, criticising the plan to cut the pensioner winter fuel payment, demanding the end of the iniquitous two-child benefit cap, is only part of the job. We also need to win the intellectual arguments, paint the pictures of a future where it all works out, and suggest ways we can get there.

Also enjoyed a great discussion of Change Everything at the Rethink Rebuild Society at the Syrian Community Centre in Manchester. They kindly said they did not plan to sue me for copyright infringement! 😃

Killing babies with insecticide

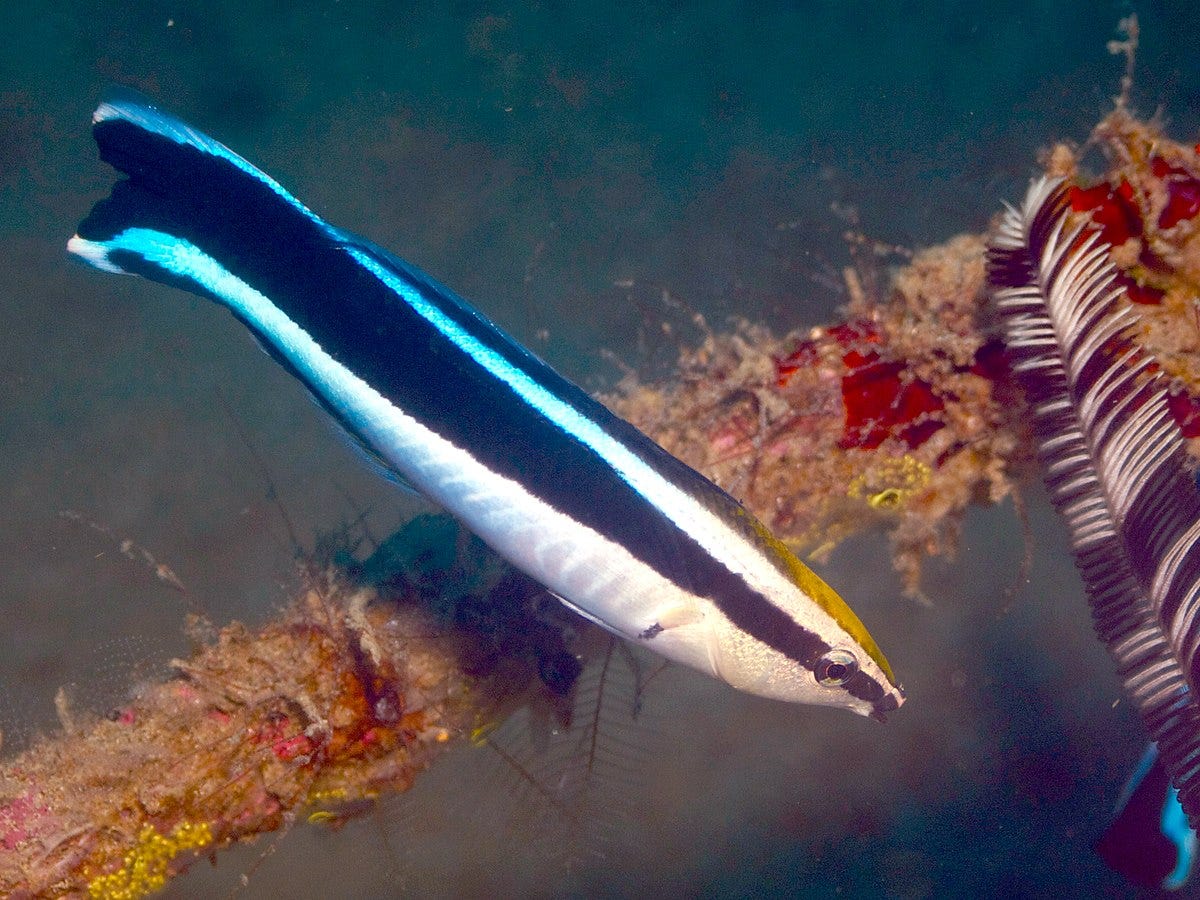

Ecosystem engineer Photo by rigel on Unsplash

There is an enormous amount of peer-researched researched published every year, the quantity doubling every 14 years or so, and a great deal of it is pure career fodder or worse. (See Retraction Watch and the replication crisis.) But every now and then, a study that is hugely informative, elegant and presents a picture of the world we are fast trashing that demands attention and sharing.

One such just out. The original is published in Science, but it has been widely covered, here with the unpaywalled Vox. It is a perfect - if awfully (in the dreadful sense) - telling explanation of the One Health principle, that human, animal and environmental health are part of one whole. And the health of people, animals and planet is in a parlous state, the product of reductionist science, colonial and capitalist exploitation. Vox sums it up:

“By compiling and analyzing a huge amount of government data, environmental economist Eyal Frank, the study’s sole author, discovered that in regions with outbreaks of white nose syndrome, a wildlife disease that kills bats, the rate of infant mortality increased by nearly 8 percent relative to areas without the disease.

There’s a clear reason for this, according to the paper. Most North American bats eat insects, including pests like moths that damage crops. Without bats flying about, farmers spray more insecticides on their fields, the study shows, and exposure to insecticides is known to harm the health of newborns.

That is enormous telling in itself - more than 1,300 extra deaths of under-ones.

Vox suggests the farmers “have” to spray more insecticide. That is if they stick with giant industrial moncultures.

Of course another response would be possible, with or without the threat of more insects following bat deaths. They could adopt an agroecological approach, smaller fields, a far more diverse range of crops, companion planting and wildlife strips to encourage other insect predators, reducing or ending fertiliser use to produce healthier soils and crops more able to protect themselves.

And even if there is anywhere the bats are safe (there is not), farmers are still spraying the same insecticides. And no doubt, young human animals are dying as a result. And no doubt also many are not dying, but suffering damaging effects. For there is no sudden magic cutoff figure for safety of these poisons. They are going to do damage far beyond their target species at any level they are used.

US chemical regulation is notably terrible by Global North standards; but there will be effects everywhere insecticides and other pesticides are used. Particularly in the Global South. As Nick Mole from the Pesticide Action Network UK reminded Green Party conference, the UK and Europe still manufacture pesticides whose use they have banned themselves, and ship them to the Global South. And as even the Telegraph noted this week, there are about 140,000 deaths annually from suicide by pesticide poisoning, although in a rare bit of good news, Nepal is making real progress on cutting its toll.

Those are not the only poisons we are spewing out to damage the environment, and ourselves, of course. The “cocktail effect” refers to the ingestion of multiple chemicals with synergestic negative effects, but we may need a new word to think about the interaction of chemical and infectious agents. That is the thinking in this again very wise and innovative article in Nature that notes how in the Arctic, where ice is melting due to the climate emergency, releasing pathogens long held there are not experienced by animals for millennium, animal immune systems are being weakened by exposure to chemicals such as PFOS (known as forever chemicals, whose concentration can only grow), making them more likely to be the source of zoonoses that can infect us. One Health - there is no escape on this battered planet if we do not start taking care of it.

And finally, I have to wonder, how much hugely deserved academic credit will Eyal Frank get for that hugely insightful work (given I’ve been talking about the plight of our universities and the need for “slow knowledge” this week)? He earlier uncovered the impact of the collapse of vulture populations in India on human health. Surely this work should race him and his department to the top of the rankings, given his additions to human wisdom? But we all know it doesn’t work like that. Ranking algorithms don’t measure wisdom.

Picks of the week

Reading

A fascinating article in Science that does a good job of taking a balanced view of attempts to decolonialise the science and other subjects taught in Indian higher education institutions, saying 5 per cent of courses should be on traditional Indian knowledge. This is happening as a result of government direction - yes that is the Hindu Nationalist BJP government, making it a cause for concern.

Some institutions are ticking the box by making yoga classes compulsory. Nothing very terrible about that: I wish someone had taught me about yoga when I was first at university 30-something years ago; I would definitely have been healthier.

And it has led to increased teaching of India’s own science history, and its place in global innovation, such as the fascinating fact that while the rest of the world for many centuries was only using zinc alloys, being unable to produce the pure metal, in the 12th century:

“People of the Bhil tribe of Zawar had found a way to distill zinc by smelting ore in a closed furnace. The region became the world’s first production site for the corrosion-resistant metal, enabling its wider use in coins and tools. British records of the method may have influenced William Champion, a British metallurgist who patented zinc distillation in 1738”.

But what is “Indian knowledge”? Will all of the many diverse cultures of the Sub-Continent be included? “Anita Rampal, former dean of education at the University of Delhi, … it doesn’t adequately acknowledge “the plurality of the region and the legacy of robust knowledge exchanges over millennia.”

Embodied thinking. Photo by Jared Rice on Unsplash

Listening

I have to say the podcast I am about to recommend is frustratingly short, but I guess the New Books Network discussion between Faizah Zakaria and Colum Graham reflecting on the power of everyday religious practice to shape the Anthropocene, which is about the former’s book, The Camphor Tree and the Elephant Religion and Ecological Change in Maritime Southeast Asia did its job, in that it made me determined to track down the text and read it. And it made me look up the story of the elephant who attacked a train - sad but telling: nature has often tried to strike back against our destruction in a multitiude of ways. (Zakaria notes that there is no way of telling whether this was a male or female elephant.)

Thinking

It is good to see researchers taking on the big challenges, like “being able to accurately measure where phosphorus has accumulated in the fewer than 100 years since humans began to increase the amount of the nutrient element in the biosphere”. Yes, you might think, maybe we should have thought about that when we started applying it, and setting out on the course of pushing our waters and soils to crisis point (“We’ve long since crossed the red line on phosphorus pollution and the effects on the Earth have been devastating,” says the UN Environment Programme) but we are where we are. Researchers point out that the phosphorous in soils, even if applied in accessible, soluble form, has often been chemically converted into other forms. Would really like to see some more indications in this article that there is associated thinking going on about how to allow healthy soil microbiomes to extract that for plant use, rather than applying more.

Researching

Checking out the opposition: source

That we have massively under-estimated non-human animals is now glaringly evident. Everywhere we look, we find levels of sophistication we once hubristically allocated only to ourselves, or at most to the apes. Thus with bluestreak cleaner wrasse, not only shown to be able to identify themselves in a mirror, but likely able to size up - literally - themselves an an opponent before deciding whether to engage in a fight with a fellow little fish, suggesting they “possess some mental states (e.g., mental body image, standards, intentions, goals), that are elements of private self-awareness”.

Yet we have to be careful in trying to learn about ourselves from animals. Must admit that I took a step back when I read Spiny mice point the way to new path in social neuroscience, particularly "We hope that our work paves the way for new insights into complex social behaviors in a range of mammals, including humans." Extreme reductionism anyone? Do we really think that a change in “neural mechanisms” is the key to social living? Might it not be a lot more complicated than that? Reminder: animals are not machines - it is long past time to bury Descartes on that subject.

Almost the end

Going on my must-read list is a book about Captain Cook’s voyage down the east coast of Australia - from indigenous perspectives. My next Substack will be focused on an indigenous perspective of the Western Desert of Australia, an area that is perhaps the most researched area of First Nations life on the continent. Great to get the view in the Cook book from the region in which I grew up.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

Your headline 'One Health' immediately caught my imagination. What a great way of succinctly explaining the interconnectedness of all life. Thank you for a great blog!