Change Everything No 22: Humans are the masters of unintended consequences

Of rats and men, and how one Baptist was disastrous for the long-beaked echidna

Book news

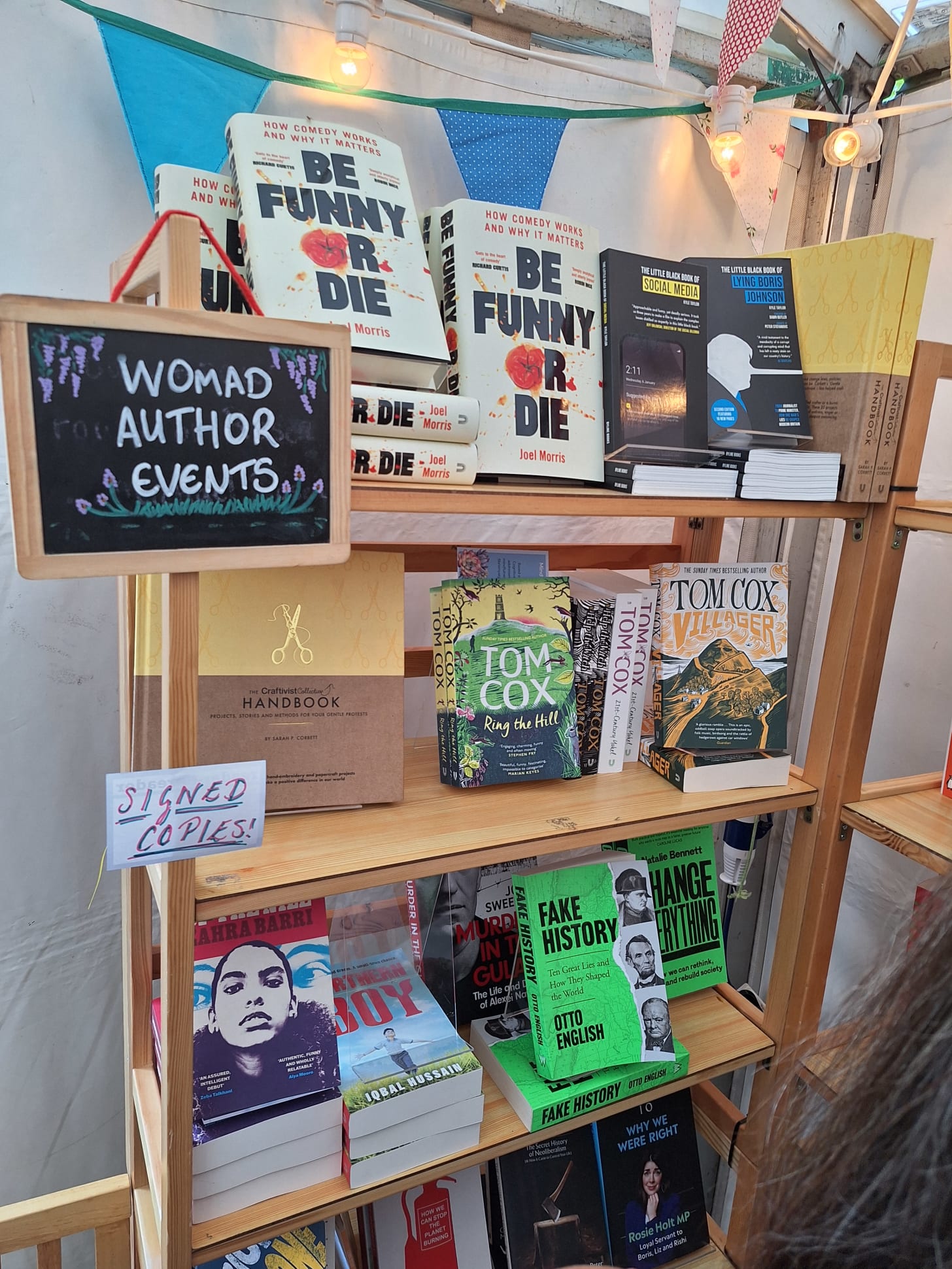

Had a lovely time yesterday speaking at the Byline Times-curated “World of Words” tent at the Womad festival (with bookselling - see below - provided by the brilliant Mr B’s from Bath), interviewed by Rachael Kerr. Next up in the festival line will be Wigtown in September. But you can always buy through Hive!

The species of unintended consequences

Human animals are good - or rather bad - at unintended consequences. My Australian origins mean that cane toads have to at the front of my mind on this subject: introduced in 1935 to eat beatles on exotic sugar cane crops, they not only failed to do that, but exploded destructively and poisonously across the landscape, such that by 1950 they’d been declared a pest.

Pesticides from DDT to neociotinoids were the new wonder chemicals that would solve the problems we’d created by introducing industrial monoculture in farming until, of course, they were discovered to be massively destructive, to birds and bees and far beyond. All too often, we’ve directly poisoned ourselves, see Romans with their lead water pipes and cosmetics (even if that probably was not “the cause of the Fall of the Empire”).

We are doing right now with microplastics and “forever chemicals”. (Which are not only in our water, our clothes and our cosmetics, but also in the air.)

We also clear the way for) animals that we then persecute and treat as pests. One of this week’s reads has been the entertaining and informative Stowaway: The Disreputable Exploits of the Rat by Joe Shute, which makes it clear that the rat which, in the West at least, we so love to hate, is a creature that - like other clever, adaptable, generalist species - we’re often responsible for unintentionally allowing their populations to explode. (Although they’re not nearly so prevalent as popular culture - and commercial-interested extermination companies - would like to claim, Shute says.)

Photo by Nikolett Emmert on Unsplash

So much so that the latest research suggests that black rats (originally from India) have colonised Europe twice, once with the Roman empire, after which they may have disappeared, while they, and possibly the brown rats (originally from China) which have largely supplanted them in the UK, returned in early medieval times, as trade stepped up again. (Although it is hard to date rat remains - by definition they burrow down through the archaeological layers!)

I’ve been contemplating why our society is so destructive and prone to producing unintended consequences with our actions. What, in ecological terms, makes us so prone to this? We are an unusual apex predator: we’re not big or fast, or armed with vicious teeth and savage claws (not T. rex or titanoboa). Reshaping our environment has been part of our basic survival strategy for millions of years. (Stone tools date back 2.6 million years - and I’ll bet the children - and adults - started cutting themselves on them or the leftover fragments at exactly the same time.) We’ve just taken this ability to dangerous - planet-trashing - extremes in the modern world.

But the dominant Anglo-American culture that’s imposed itself on so much of the world is particularly bad at both creating messes, and blaming the creatures that flourish in the world we created. Shute points out that in their native lands the rat is far more kindly regarded and understood as a creature that has a right to exist and live its life. Fascinating that: “When it rains in Delhi and their burrows are flooded… there is a kind of rat amnesty declared for the rodents, scurrying to find new homes. People will not kill them when they are clearly desperate and in need.”

The international aspects of the book were picked up by no lesser organ than Foreign Policy, which notes approvingly that Shute suggests “we should be redirecting our distaste away from rats to the human processes that enable them”. As he does - noting that complaints about rats being a problem are extremely closely related to human poverty and misery - and tackling that is not only good in its own terms, but also far more likely to control the rats, given that if a population is reduced by 80 per cent by control measures, it’s likely to be back to the original levels a month later.

But thinking about the broader issue of Western societies creating the conditions for what they like to regard as pests, then expensively - and frequently poisonously (for target and non-target species alike) - trying to eradicate them requires a reminder that other socieites and ways of looking at the world, particularly among indigenous societies, are far more holistic, systemic — and humane.

In Tim Flannery’s brilliant Here on Earth: A New Beginning, I read about the Telefol people of central Papua New Guinea who have a native pine grove that is absolutely protected, where not even a leaf may be picked, which is home to spectacular bird of paradise. And that the long-beaked echidna, above, an up to 1m-long, 16kg, slow-breeding creature that can live up to 50 years, extinct everywhere except in the central mountains from 40,000 years ago, with the fattest and tastiest flesh of any PNG creature, survived around the Telefol because of a very strong taboo against any harm to it, on pain of disaster to the Telefol. “But then a Baptist missionary arrived in the region, and the Telefol were taught that their ancestors’ beliefs were the work of the devil. With a short space of time long-beaked echidna simply ceased to exist in the region.” Yet, Flannery points out the belief had previously been so strong that even though hunters often worked alone, and remained alone for several days, so could easily have broken the taboo without anyone know. Yet the survival of the vulnerable species showed how rarely that happened.

It is no accident that indigenous people protect 80 per cent of the world’s remaining biodiversity and forests.

A lot to think about how we want to shape the future of human culture and behaviour for a planet on which we and other species can survive and thrive. On which note, I read a fascinating prediction about the likely future direction of human populations. Varying estimates put the point of maximum human at the 2060s to the 2080s, but the maths indicate that after that, our population will plummet. If we’re truly going to start to think longterm and systemically, we need to consider what a world might look like with half the number of humans we have now, or a quarter. How might that be managed? Without - necessarily - creating a great deal of space for rats (albeit that should the some of the human race manage to far more destructively reduce its numbers through the use of nuclear weapons, Shure reminds us, the rats will almost definitely take over, due to their relative capacity to survive radiation poisoning).

Picks of the week

Reading

Author, royal tutor and schoolmistress, Bathsua Makin, pictured above, is one of the central characters in the book I am really going to get back to writing one day, a history of the women of London. She’s also got a prominent place in Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century by Carol Pal, which argues that not only was their a (quite well known) network of female scholars around Europe at the time, but that they were far more central to broader, male-dominated, networks of the time than has been recognised. This is the arc and explanation that Pal sets out:

“The middle of the 17th century was a period of world-changing instability … it was a non-stop storm of political, and intellectual ferment that filtered into almost ever sphere of existence … many of the customary social barriers did not hold … the posthumous obscurity follows very closely … Political stability began to return to Europe and Britain after 1660… the production of scientific knowledge outside the universities became institutionalised in various academies. Within these institutions, a certain level of social and epistemological homogeneity began to prevail.. the outsiders disappeared.”

Listening

Patrick McGuinness’s account of his memories of changing life in the Belgian industrial city of Bouillon - recorded for the London Review of Books podcast - is not your average childhood memoir. Not just because many people who - like me - often visit Oxford, have reflected on its discomfort with its industrial legacy, and the uncomfortable intrusion of tourism, with which McGuinness draws instructive Belgian parallels. But also for his sharp observations on the way in which women and men within the one family can come to - uncomfortably - occupy very different class positions.

Thinking

You can call this good reason to get off the couch. From New Scientist: “When it comes to starting cardio exercise as a beginner, “one of the first things that happens is you get more blood volume”, says Abbi Lane at the University of Michigan. Within 24 hours of working out, this increases by up to 12 per cent due to water retention. which increases the amount of blood plasma, boosting the amount of oxygen that can be supplied to the muscles. And as for weight training, “Everyone gets stronger in their first three weeks because your nervous system learns how to talk to your muscles better.”

Researching

How could multicellular life have begun on “Snowball Earth”, around 700 million years ago, when the whole planet was essentially like polar regions today? A fascinating new theory suggests it is because in sea water that turned viscous in the chill, single cellular organisms clumped together so that they could move and more easily find food. That’s what modern Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (a motile algae) do.

Almost the end

Wht did titanoboa pop into my head? I’ve been listening to the latest Common Descent podcast on boas and pythons. Particularly fascinating on new discoveries about how constructor predators actually kill - the traditional story is by constructing the ribcage and hence the lungs, but apparently more commonly it’s the unbalancing of blood pressure that brings on a heart attack. Something to consider should you find yourself in the coils of an anaconda (actually extraordinarily unlikely).

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

You may have misread the Smithsonian article that says "Spanning the past 2.6 million years, many thousands of archaeological sites have been excavated, studied, and dated" to conclude that stone tools date back 2.6 million years. Some of the sites may be that old but the tools cannot. Humans only evolved in the last half million years.

Reading, listening, thinking, researching and caring about people and planet. Thank you Lady Bennett for helping me a busy mum Of 2 smalls do a bit of the same as i read this, whilst also half listening to CBeebies. An interesting juxtaposition!