Change Everything No 21: Radegund, a woman of power in a dangerous world

The 6th-century Merovingian kingdom was a place in intrigue, torture and violent death. But women stood together and resisted

Book news

Lots of Change Everything book events still coming up. I’m speaking at the Womad festival on Saturday, and while I’m trying to stay away for August (trying to get the next book written - more on that soon), dates for September to watch out for include Diss September 3, the Trouble Club in Manchester September 5 (bookings here), the postponed event at Hull Wrecking Ball Music and Books on September 11, Lighthouse Books in Edinburgh September 26 (which you will also be able to attend remotely), the Wigtown Book Festival (September 28) and hoping to set a date for Stanfords Bristol soon. If your local bookshop might be interested, please tell them to get in touch.

And further good news is the second printing of Change Everything is now widely available (from Macmillans Distribution), including my online favourite Hive, in print (£9.59) and e-book (£4.19)

Radegund: a woman of power in a dangerous world

With everything going on the in the world, why should I be reflecting on a biography of a 6th-century Thuringian princess, Frankish queen and nunnery founder and saint? (Radegund: The Trials and Triumphs of a Merovingian Queen, by E.T. Dailey)

Well, there is the fact that Radegund is an impressive, fascinating character, operating in Merovingian society (largely in what is today France) that if it wasn’t the inspiration for King’s Landing in Game of Thrones certainly could have been. We all need an escape from the present sometime, and my preference is for non-fiction rather than fiction.

But more than that, it reflects the importance of understanding the past - undoing many of the past and continuing stereotypes about it - as a way of influencing the present. This particularly important when the humanities are under attack in universities across the world - the scholars sacked, the courses dumped - as I was discussing with some of those affected last week.

That as I reflected on Donald Trump’s selection of JD Vance as his vice-presidential running mate (and potential president - let’s not forget Trump is 78 years old). I read about Vance’s neo-conservative intellectual influences, as Politico identified - unsurprisingly all of the named figures being male and many of them influenced by rightwing Catholic theology.

It came together with questions put to me during a school visit to an area of the country “left behind”, where I found extremely politically engaged, thoughtful and rightfully rebellious young people being clearly exposed through social media to a range of disturbing American far right thought. Did I think Project 2025 was right about the way to “advance” women, one girl asked? “Advance” meaning “a clampdown on federal funding for abortion, the removal of "gender equality" language from government websites, and reducing access to contraception”.

Built into that ideology is a claim that in the past women were silent, mild, didn’t answer back, followed the direction of husbands and fathers, and were better off for it - rather like the mother-of-eight “Trad wife” interviewed for yesterday’s Times, who couldn’t seem to get a word in edgeways, despite the reporter’s best efforts to give her a voice of her own.

That was very definitely NOT Radegund. She started as a captive as a child, in the hands of the king Chlothar, who then decided to marry her. She wasn’t hooked into networks of women that could protect her, but those networks certainly existed, and were powerful.

“Radegund’s prospects of escaping marriage to Chlothar were bleak. She lacked a powerful advocate to persuade the king, perhaps through generous gifts, to see to her release. She was not as fortunate as Rusticula, for example, who had initially suffered a similar fate. Abducted at the age of five, by an aristocrat and kept within his home, Rusticula was watched over by the man’s mother until she was old enough to marry. Her fate changed when the abbess Liliola asked King Guntram to intervene, so that Rusticula might instead be entrusted to her convent at Arles. .. the presumably grateful Rusticula later refused the attempts by her mother and her kin to see her returned to her aristocratic family in Vaucluse. She opted instead to remain within the convent, where she eventually became abbess herself.” (p. 23)

An 11th-century depiction from Bibliothèque municipale de Poitiers

Yet on Dailey’s reading, when she was forced into that marriage, Radegund did it on her own terms. Rather than the ceremony being in a quiet backwater, unknown to the court and the world, which could have seen her treated as a concubine rather than a queen (the Merovingians weren’t really into monogamy), she fled her captivity to the centre of the action, and ensured the ceremony took place there.

When the Chlothar killed her brother, however, Radegund had had enough. And escaped into the church. As Dailey says:

“Radegund lived during an early era of female asceticism, distinguished by its diversity and creativity. … Radegund may be best remembered for founding the convent of Holy Cross, a formal religious house for women that represented an important contribution to the professionalization of female ascetic practice in central and northern Gaul, but when she first left Chlothar’s side, she fulfilled her religious vows in a much less formal setting. In the villa of Saix, in the region of Vienne (10km south of the eoponymous river’s confluence with the Loire, Radegund lived as a woman avowed to God and committed to pious service and personal elevation, yet also as a royal woman in retreat on a country estate…. She hosted bishops and sent them away laden with gifts. She distributed bread to the needy, made out of flour that she ground herself. She washed the poor with her own hands (the whole bodies of women but only the heads of men) and applied oil to their sores. Women who arrived in dirty rags departed in new clothes. The poor came hungry and left fed…..When a group of lepers arrived… Radegund rushed to greet them and arranged a feast. She wrapped her arms around leprous women and kissed their faces, to the great alarm of one of her attendants.”

Radegund enjoyed a clearly close relationship King Sigibert and his queen, Brunhild, who sent the fascinating figure, poet and writer Fortunatus, to her, one reason why we know so much about her life. (Another is a “life” written by one of her successor nuns, Baudonivia - the level of literacy in the nunnery was high.) Brunhild enjoyed an active, effective life. Her end, however, was very Game of Thrones: Captured by Fredegund’s son in 613, Brunhild was tortured for several days, paraded around on a vamel, and tied – by her hair, an arm and a leg – to the tail of a crazed horse, which tore her body apart when it bolted. (p. 85)

I’m not going to venture into the theological or practical details, but what’s fascinating about Radegund is how she carves out, in the midst of all of this, a clearly huge and influential place for the nunnery she founded, including securing “pieces of the True Cross” (yes, I know, but it mattered at the time), as a gift from the Eastern Roman Emperor, and a special place for her nunnery outside the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Unfortunately after her death, internal conflict in the nunnery saw those powers eventually taken away, but it remained an important institution and her memory was treasured.

In the later Middle Ages, the people of Poitiers regarded St Radegund as a protector, drawing on a story that she had expelled a giant winged serpent with an enormous mouth that had been consuming inhabitants. “In the 1460s… the abbess Isabeau de Couhe unfurled a banner with the image of a dragon, a reference to the vanquished serpent, to demonstrate her authority to a group of local clerics who, though traditionally in the service of the abbess, had nonetheless come to consider it ‘against nature’ to have a woman as their superior. By 1666, any doubters of the legend had to reckon with clear proof, in the form of a stuffed crocodile, displayed on a wall of the Palais des Comtes. The specimen was mentioned by the young Lord Fountainhall, wrote wrote in his journal that the beast had once been much larger, but had diminished in size over the centuries.” (p. 1)

Of course Radegund started with the advantage of elite birth. But the nunnery must have been a refuge for many women from a range of backgrounds. And the servants of queens and princesses, their kin and friends, were no doubt - in ways now unrecoverable - able to hook into these networks. Much as we need today as women to network together and support each other - and share stories about powerful women.

I can imagine (although not going to write - giving away the idea for free) an alternative history in which the many powerful women in the early Catholic Church face down the misogynists, secure and retain powerful places for themselves, and set Europe on a different path of gender relations. As another book I’m reading now, Zrinka Stahuljak’s Fixers, reminds us, when looking at medieval history, modernity is the uncertain future. History is not pre-written, but made by the actions of people.

Picks of the week

Reading

I was reminded this week about my liking for the 2018 film The Favourite, about the reign of England’s Queen Anne (unusual, because movies are really not my thing - there are too many books in the world). But the reason I was attracted to The Favourite was because more than most history films, it captured I think something of the chaos and confusion, the muck and the sleeze, the pure happenstance of history that is all too often tidied up into clean, neat textbook narratives. So it is with a rare novel I read this week, The Heart in Winter by Kevin Barry. A Western, but nothing like a traditional piece of that genre. The Guardian review captures it well. Definitely a gripping, evocative, powerful read that will stay with me.

Listening

Important reflections on the current witchhunt against trans people: On the New Books Network a discussion of the fight to remove homosexuality from the official - and highly influential - US list of pathologies. And how others got left behind, or pushed out, in the drive for respectability.

Thinking

An encouraging article in New Scientist (sorry £, but your library should have it) acknowledges that while we still don’t have a clear definition of consciousness, research is increasingly demonstrating beyond doubt that many species have it,and that its presence should not be regarded as reflecting a hierarchy, with humans at the top. (he New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, now with more than 300 signatories.) It concludes: “For too long, we assumed that humans are unique and animals don’t feel pain or emotions the way that we do, a convenient but cruel null hypothesis, when we could have started from the position that perhaps they do instead.”

What are you thinking? Photo by K. Mitch Hodge on Unsplash

Researching

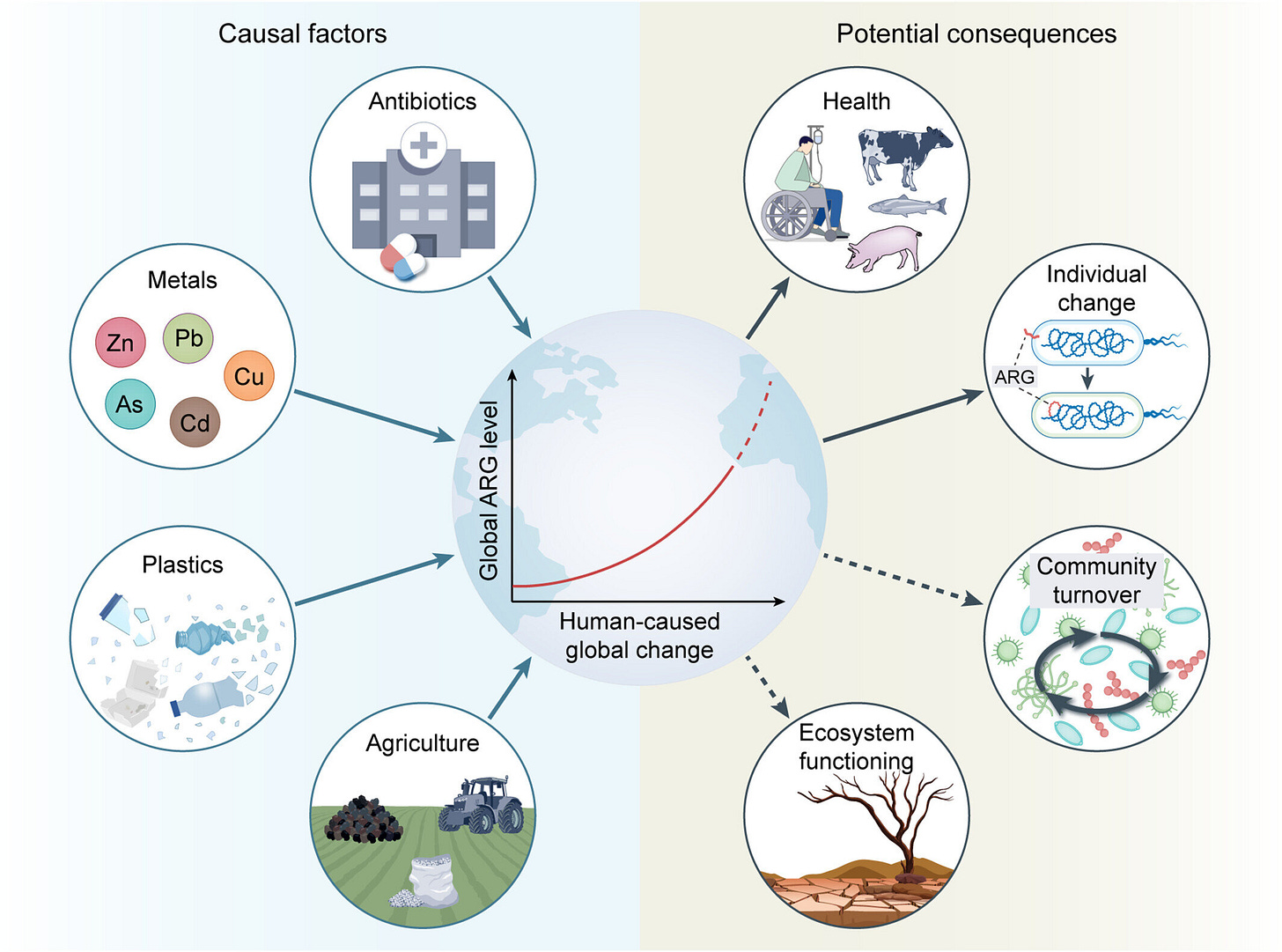

Antimicrobial resistance is an issue that (working particularly with the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy), I do a lot of work on. Reflections on a report out of my office prepared by Dr Paul-Enguerrand Fady have just been published by two eminent reserahcers in the British Journal of Nursing. But this research, which posits that the increased number of antibiotic resistant geners *ARGs) is itself a factor of global change takes reasons for concern on to a bigger scale. (And I think that should be antimicrobial rather than “antibiotic” - don’t forget the fungi!)

Global Change Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1111/gcb.17419

Almost the end

Wondering about Radegund’s English connections? Well she’s the patron saint of Jesus College, Cambridge, and she also has her own pub nearby!

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.