Change Everything No 16: Where's the recognition for community rights?

Chatting with Kate Raworth, questioning the nativity scene, and giving up the Sunday roast to help pay for a community hall

Book news

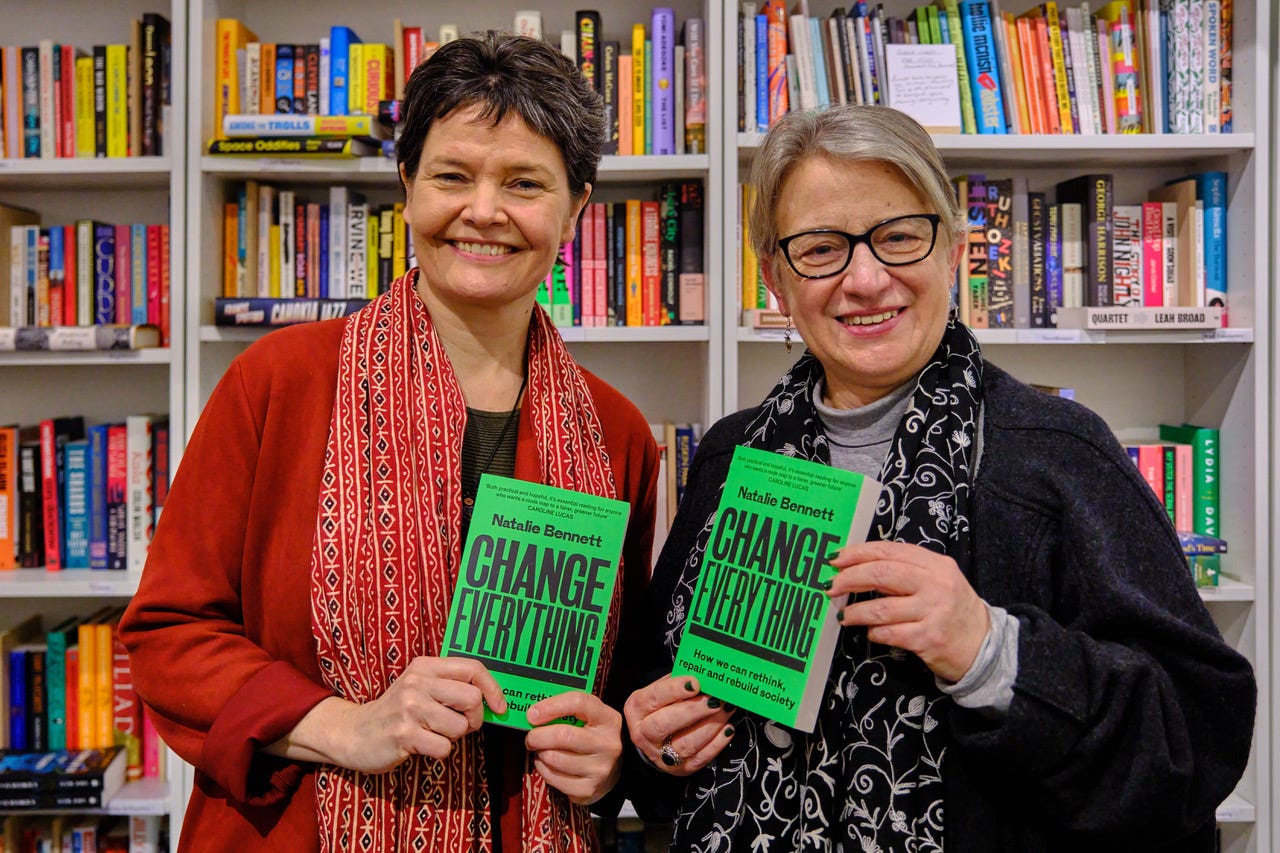

Sorry for the two-week break in Substacks. It has been a busy time, culminating in a lovely Oxford launch of Change Everything the book (the ebook now available from Hive at a bargain price of £4.49), with me in conversation with Kate Raworth, which was just a delight - at the lovely new Caper bookshop. Thanks Hugh Warwick (@hedgehoghugh) for the pic!

Also enjoyed doing an excellent All Talk podcast, about Change Everything and politics in general, with LBC’s Iain Dale, and an hour-long phone-in on his programme that was particularly notable for the degree of listener support for my arguments for a school system providing an education for life, not just exams. And talked over the culture chapter and more with Tom Platts of the Making an Impression podcast.

Picks of the week

Reading

Heresy: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God by Catherine Nixey is just enthralling, and enlightening. And will give you tales to tell many Christmases hence: why are there an ox and a donkey overlooking Jesus’s cradle in classic Nativity scenes? They are not from the modern Bible, but from the Infancy Gospel of James, eventually dismissed from the canon. (In it Jesus is born in a cave, not a stable).

Heresy? Photo by Walter Chávez on Unsplash

For less polite occasions, why for centuries were there debates about whether or not Jesus defecated, and about not just virgin conception, but virgin birth? (Think about it; rather hard to achieve.) But what will really stay with me is the impact of Christianity in changing the use of the title term:

“Heresy came to be closely associated with Christianity, but as a word long predated it. ‘Heresy’ comes from the Greek word haireo, which means ‘I choose’. In the form ‘heresy’ - haeresis, in Greek, it merely meant something that was chosen; a ‘choice’. In the pre-Christian Greek world, ‘heresy’ had been a word with positive connotations - to use your intellect to make independent-minded choices was, then, considered a good thing. It did not retain that positive feel. Within the first century of the birth of this new religion, ‘choice’ for christians had become … a ‘poison’. Heretics started to be spoken of not merely as people but as a disease to be ‘cured’, a gangrene to be ‘cut out’ and a pollution to be eliminated in order to purify the Christian body as a whole.”

More in the Guardian review.

Listening

The Common Descent podcast is always a delight, but found the episode on cacti a particular pleasure. No, I didn’t know that cacti are only originally found in North and South America, except for one species, Rhipsalis baccifera (mistletoe cacti) which is also found in Africa and India. Dr Baumgartne, the show’s plant expert, is definitely in favour of the “birds distributing” theory. Also fascinating is that while genetics suggested cacti evolved 30 million years ago, the oldest fossils are just 24,000 years old. A reminder that when we are reconstructing ancient ecosystems, we’re heavily biased towards what was preserved.

Thinking

"I’m putting forward a paradigm shift. And the critics are saying ‘we don’t want a paradigm shift, we’re fine, just the way we are’. We’re not fine.” - Suzanne Simard

A familiar story in science, particularly for women. The pioneering forest ecologist who introduced the idea that has been popularised as the “world wide wood” - and the “Mother tree” - has come under concerted attack from scientific traditionalists. (Very much reminds me of the treatment of Lyn Margulis - who I wrote about in Change Everything No 4.) The debate - which can be simplified down to those who see nature entirely based on competition and those who want a strong element of cooperation - gets a fairly balanced workout in Nature this week. Well worth a read. And at least there’s no argument that fungi getting a lot more attention is really important.

Photo by Emma Gossett on Unsplash

Researching

All too often, even now, researchers and writers who should know better think of people of the prehistoric, pre-agriculture, past as living simple, humble, limited lives. (Yesterday I stopped listening to a podcast when the academic speaker suggested that in the past we all lived in small families and clans and never moved around or changed cultural identities. Not going to point to it; not worth listening to.) Yet meta-research into the archaeology of people living across what is now Europe from 34,000 to 24,000 years ago shows complex cultural choices and patterns.

Some groups preferred making beads from deer teeth, others from fox teeth, even though these would have been equally available to both. Sometimes this linked up to genetic similarities, sometimes it didn’t. Sometimes people had jewellry suggesting they had moved hundreds of miles into different cultural areas. Burial practices changed significantly over time. It shouldn’t need saying, but it does: they had cultures, they made choices, they mixed and matched - they were just as smart and creative as us. And bling has always been a thing, as the reconstructions here show.

Where’s the recognition of local contributions?

It might be that Thames Water comes to be seen as the crowning disaster of the privatisation agenda; certainly the perilous financial state of the heavily debt-encumbered, leaky (in the real sense) company has been all over the headlines this week. That together with the threat of everyone in its region having to pay a heap more just to cover for the greed and over-reach of the financial sector, which is pretty much the story of the past decade-plus of austerity. I was on LBC with Natasha Devon tonight, reflecting on how Labour’s focus on potential criminal charges for water bosses shows a lack of understanding that the whole system is broken.

But I’ve been looking at the smaller scale disaster of the loss of public facilities from local communities, with a visit to Croxley Green, near Watford, a small community with a big problem. It turned out in its scores for my visit, to defend a modest but hugely important building, the Red Cross Hall, threatened with re-development for flats.

Speaking to older residents, I heard how when the hall was built, the Red Cross didn’t quite have enough funds to complete the building. So the locals jumped in to support. Two shillings and sixpence paid for each brick, and many families found the money by skipping the culinary highlight of their week, the Sunday roast.

Facilities like these should belong to communities, yet all too often the ownership is in distant bureaucratic or even privatised hands that sell it off with barely a nod to consultation. This first really struck me a decade ago on a visit to the Isle of Wight, seeing the once beautiful (and could be again) Frank James Hospital, built with charitable funds as a retirement home for mariners, converted into a hospital with considerable donations from local businesses and workers. When the NHS was founded it was rolled into that, and the locals lost any say over the facility they’d had a big part in bringing into existence.

It is an extreme case of what I’ve seen in every community I every worked in. When a local hospital or other community facilities needs a fit out, wants a special improvement, often it is cake sales and volunteer car washes, bingo nights and raffles, that raise the cash. Yet somehow, when a sale is on the agenda, none of this is taken into account.

Green political philosophy is founded on local decisionmaking, with power reflected upwards only when absolutely necessary. These case studies are a powerful argument for such a model of local control and local collective ownership, which both acknowledges and encourages community contributions and strength.

That’s something we need to do also on a larger scale. Our current infrastructure and facilities were built by the communal contributions of communities. They are our heritage. Selling off “the family silver” has to end, and, whever possible, be reversed.

Almost the end

To finish on a positive note, I was really excited to see an exhibition of the works of Mary Beale (work above), arguably England’s first professional female portrait painter, coming to London - with an expansive online catalogue. (Although since she’s the subject of a completed chapter of my currently on-hold book project on the history of the women of London, I’m afraid that means a lot of updating!)

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.