Change Everything No 31: Astrobiology - finding ourselves in space

Reading Nathalie A. Cabrol's The Secret Life of the Universe

Book news

Looking forward to joining Nottingham Green Party tomorrow (Monday) night to talk Change Everything, the book. And Tuesday week at the People’s Bookshop in Durham. If you’ve read a copy and enjoyed it, please do let the world know about it!

There is potential for life in the oddest corners of the universe

Astrobiology, as a field, is about as old as I am, starting in the early 1960s. Nathalie A Cabrol in The Secret Life of the Universe begins by describing it as “the search for life in the universe”, but it is really about much more than that: there is plenty of hard science, astronomy, physics and chemistry in it sure, and the biology of trying to understand what life is (and realising that we have no real definition about that on Earth, let alone further afield) - but it is also about philosophy and anthropology and history - trying to come to terms with ourselves as a complex but still ignorant species slowly overcoming a period of dominant hubristic simplistic thinking. We are slowly realising how little we understand and how much we are at the mercy of forces far beyond any capacity we have to defend ourselves against them.

The Secret Life of the Universe is a survey for a general audience, but set at a high level. Starting with life on Earth this book, published 2023, gives a quick run-through of our understanding of the earliest life Earth - possibly as old as 4.28 billion years ago in what was an ancient oceanic floor now in Canada, barely 200 million years after the surface of our planet had solidifed. Certainly there is evidence from hot spring and vent deposits 3.5 billion years ago, along with the Strelley Pool fossils from a shallow sea now in Autralia from 3.43 billion years ago. Their ancestors had survived the late Hadean eon (yes that is a reference to Hades and hence hell) - a time of rampant volancism and regular bombardment of the planet from enormous asteroids and comets, which might well have blasted debris into space, producing “winters” that could have lasted for centuries. (pp. 28-30)

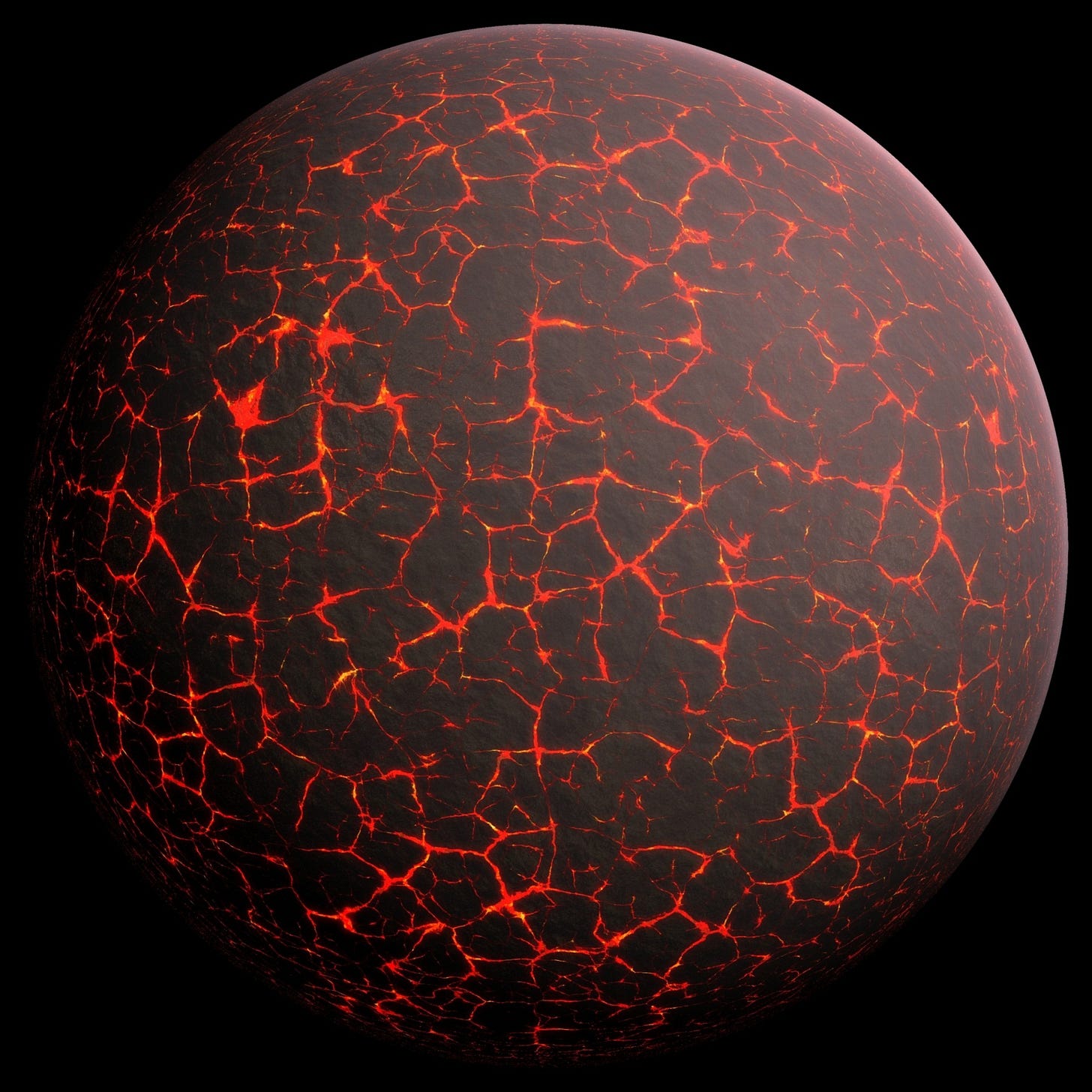

Before life, probably. Source

About 4.5 million years ago a collision or series of collisions (the theories are set out) created the moon. Which was crucial. “The formation of the moon certainly played a central role after life took hold, as Earth’s seasons produced by the axial tilt directly drive life’s rhythms, metabolisms, dispersals, migrations and speciation over time.” (p. 32)

Even as things started to settled down in the Archean (3.8 billion to 2.5 billion years ago), the sun had only 75 per cent of the power that it provides now, and there should not have been any liquid water on the surface, which we think is essential to life. Yet life there was, possibly helped by fewer continental masses reflecting light back into space, and an atmosphere rich in carvon diocide and methane, which might have maintained the surface temperature above freezing. (p. 18)

This is still a very, very different planet. And we have come a long way in understanding it, helped by life.

“About 1.5 billion years back, the moon was still close enough for a day to last only 18 hours, and not so long ago, a year was still 420 days instead of the current 365 days. These changes are preserved in 430-million-year-old fossilised corals. Just like trees, corals record their growth in layers. When a coral grows, it accummiulates a fine later of calcium carbonate every day, and its monthly deposits are linked to the lunar cycle. Seasonabl changes are visible too… Dueing the Silurian period (444-419 million years ago) a day would have lasted about 20 hours. A few million years later, other fossilised coral records from the Devonian period (419-359 million years ago) show that the Earth’s spin had slowed down to 410 days per pear. A day then lasted about 21 hours. As the Earth continues to slow down, its rotational energy is being transferred to the moon, causing it to pull away from the Earth about 3cm a year…. the length of a day … 25 hours long 180 million years from now.” (p. 32)

A blue moon - for now. Photo by Doug Walters on Unsplash

But of course, the origins of life might not be on our planet. They might be multiple, or singular from elsewhere and spread to us, or our planet could have spread the seeds. “Among the lunar rocks collected by Apollo 14, one contained traces of minerals with a chemical composition typical on Earth and unusual for the moon. It may have originated from our planet and was blasted off to the moon when the Earth was strick by an asteroid 4 billion years ago.” (p. 148) Martian meteorites have been found on Earth, and fragments of asteroid Vesta on asteriod Bennu “show that this is a universal process that can take place with objects of all sizes”. (p. 152)

Panspermia - the idea that life did not originate on Earth but outer space - was a concept originated by the Greek philosopher Anazogoras (500-428 BCE) and it was revived in recent times by the chemist Svante Arrhenius in 1903. Carbol’s conclusion? “It seems like a more real possibility today, but understanding whether it is the primary vector for seeding life in the universe or only an occasional contributor will take more time to figure out.”(p. 152)

That of course takes us to the big question of astrobiology: is there other life out there, or more immediately pressingly, is there other intelligent, technological life out there, what could be our peer, or our rival on some accounts? You’re probably familier with SETI, but may not know about METI - or that there are currently no standards, not even voluntary standards, about making attempts to contact it (as discussed in this New Books Network podcast). And that brings up the fascinating idea that there might be ETs out there, watching and waiting to see whether we get beyond destructive toddlerhood to a more constructive and cooperative adolescence, when it might be safe to contact our species.

After the initial chapters, we do get off Earth (and away from the moon), running through the many amazing discoveries of the past decade or so, through both telescopes and far-reaching space probes, which have essentially rewritten our understanding of our neighbourhood - in the universe sense. Essentially, as Carbol presents it, the possibility of conditions for life (even as we understand it in carbon-based forms) is appearing in many places that only a few years ago would have been thought impossible. And there’s also a note as to why we don’t get exciting reports about discovery of Earth-like planets outside the solar system any more (I’m old enough to remember when we did). They’re just so commonly found now as to be unremarkable except to specialists.

Often this is told as an adventure tale - and Charbol does a fine job of painting a picture of how it has been done, and the nail-baiting wait for news from a far distant vessel. Take the arrival of Hujyen on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon:

“We already knew that weird prebiotic chamistry could be taking place and possibly give rise to life as we do not know it on the surface but the existence of liquid water at depth opened new possibilities. Titan increasingly looked like the perfect alchemist’s cauldron… a natural lab… It could allow us to start cutting out teeth on a completely alien, methane-based biochemistry. But that was not Hugyen’s mission …Unlike the Mars rovers, the Hugyens prove would not rely on high-resolution data for the selection of a landing site before the miission, or much data of any kind to begin with. The probe was thus designed to survive both a hard landing or a splash landing in one of Titan’s seas and to last long enough to collect some data on the ground. .. the probe probably came to rest on a riverbed covered with cobbles made of hydrocarbons and water ice. Rocks made of solid water ice rolled and rounded by time in torrents of liquid methane.” (pp. 116-8)

Titan, seen by the Cassini probe. Nasa

But of course, we keep coming back to Earth, and the mess we are making of it. And for that, Cabrol has many interesting perspectives, not least that life has smashed up its environment before in “one of the worst ecological disasters in history that followed the release of oxygen into the Earth’s atmosphere by cyanobacteria a few billion years ago. The Great Oxygenation Event killed 90 percent of all life on Earth and altered the environment forever, including our planet’s signature in space.” (p. 254)

I am used to thinking about the long duree of history - my next book takes a 300,000-year view of our history - but this is taking it on to another scale altogether. I’m reminded of Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s Total Perspective Vortex: but, as Cabrol outlines, with images of our planet from space, we have - or should have - begun to grasp - what a fragile place we exist in, and how we urgently need to look after it. Disorientating ourselves, as this book does, imagining our planet in 100 million years - or a billion, when it will become uninhabitable - might just help us to re-form ourselves in our current fragile moment.

Picks of the week

Reading

I have been revisiting Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us, from which I took some notes. And you might guess that the horrible behaviour of the title comes from Homo sapiens, while animals perform the most amazing feats of care and ecological management. I just love this: “Even moth parasites control their populations to protect the habitats they rely on. Dicrocheles mites live in the ears of noctuid moths. Although their occupation means breaking through the tympanic membrance, which results in deafening the moth’s ear, they will never migrate to the other ear. That would not do for a moth who needs to detect the echolcation calls of hunting bats … the mites send scouts across to the clear ear to lead any stray wayfarers back home.”

Listening

I don’t necessarily 100% agree with it, but I thought the perspectives in the New Books Network podcast on The Spectre of State Capitalism were well worth an hour. “How do contemporary state-led economic initiatives compare to the heyday of Keynesian and developmentalist policy agendas in the decades immediately following World War II?” Which is a reminder to the neoliberals that the multinationals of today got a huge handup from the state in multiple ways.

Thinking

We have a world profoundly out of balance, and the damage done in one area rebounds through many others in hard to predict ways. That was elegantly - if frighteningly - demonstrated by research into the decline of seed dispersing animals on European plant species. We’re used to worrying about pollinators, but this is a whole other set of relationships to be concerned about.

Photo by Steve Smith on Unsplash

Researching

The impact of “novel entities”, the multiple compounds our chemical industry is pumping into our planet with scant understanding of the consequences, is something that occupies quite a bit of my political time. (I’ve got a question in the House this week on biocidal products in hand and body products.) Researchers have been looking into the impact of a pretty standard list of personal care products: “roll-on deodorant, spray deodorant, hand lotion, perfume and dry shampoo hair spray—all produced by leading brands and available in major stores across Europe and elsewhere. on indoor air quality. The thing is, in the home, the volatile compounds they contain don’t just stay on their own, but often combine with other substances, the results ending up in our lungs. One researcher said: "In my opinion, we still don't fully understand the health effects of these pollutants, but they may be more harmful than we think, especially because they are applied close to our breathing zone. This is an area where new toxicological studies are needed."

Almost the end

Good news: BHP this month is to be held to account in a UK court for the Mariana Dam collapse. I’ve met some of the claimants; I wish them the very best of luck.

What did you think?

You can also find me on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, TikTok and X.

You may be interested in this really interesting piece about the impossibility of humans living anywhere but Mother Earth https://medialens.substack.com/p/expanding-beyond-earth-the-illusions